The Godfather Speaks

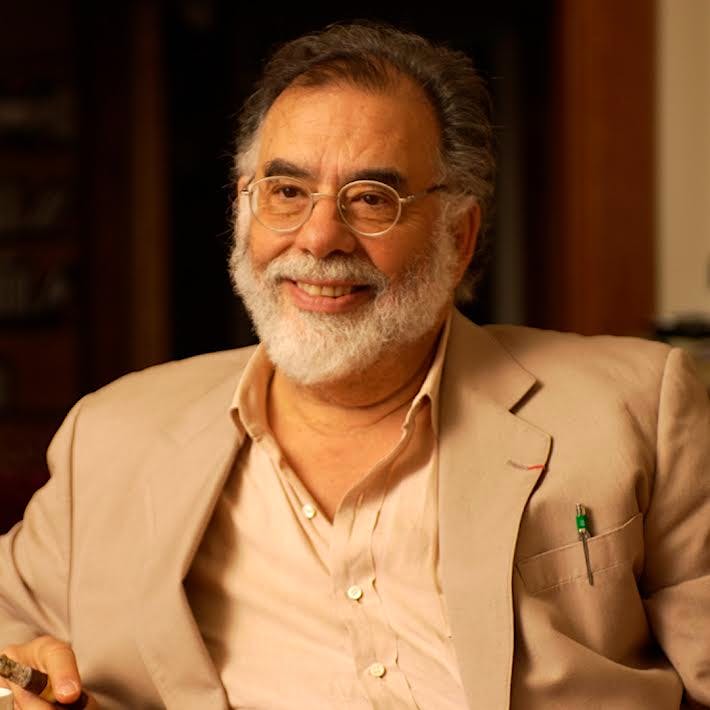

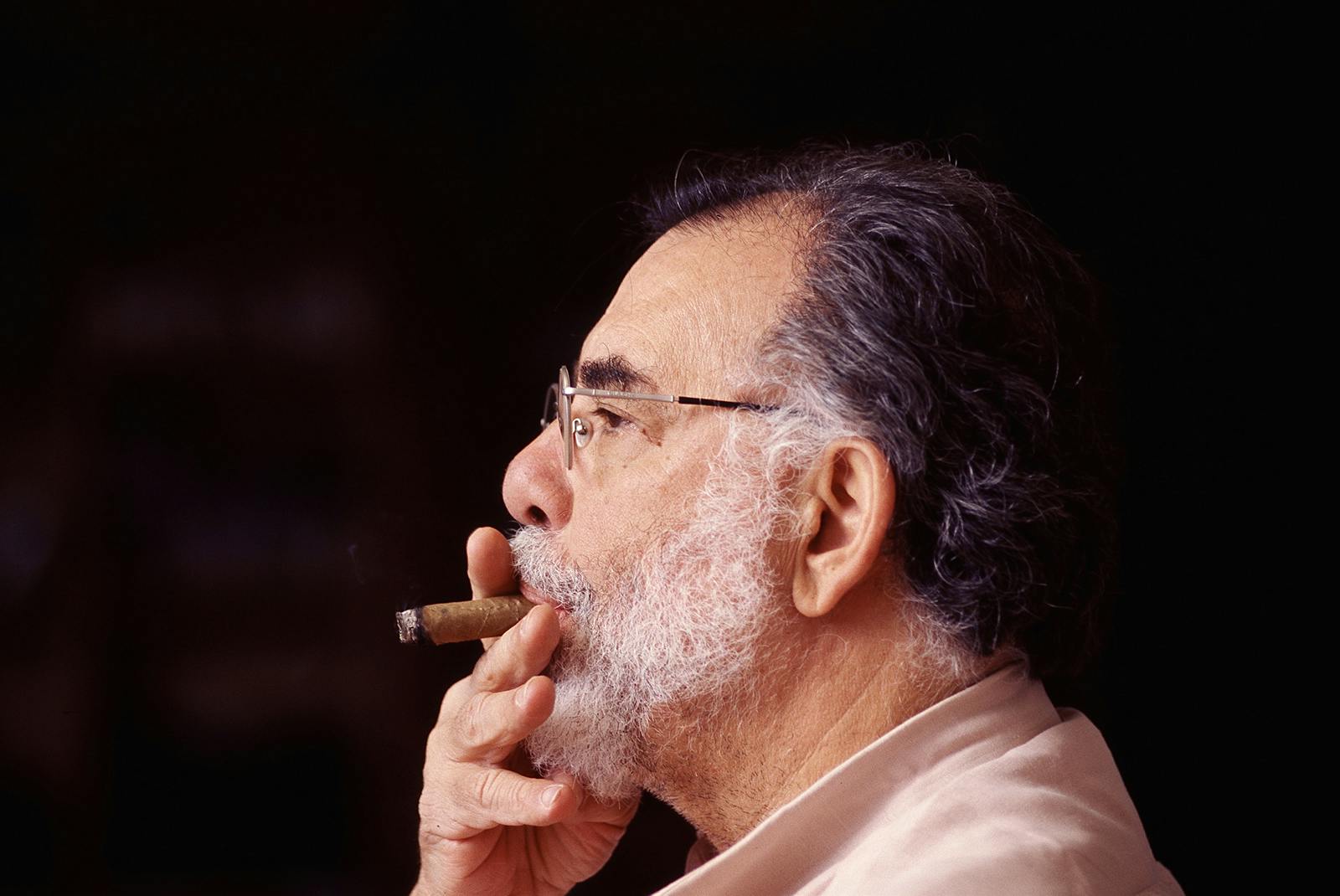

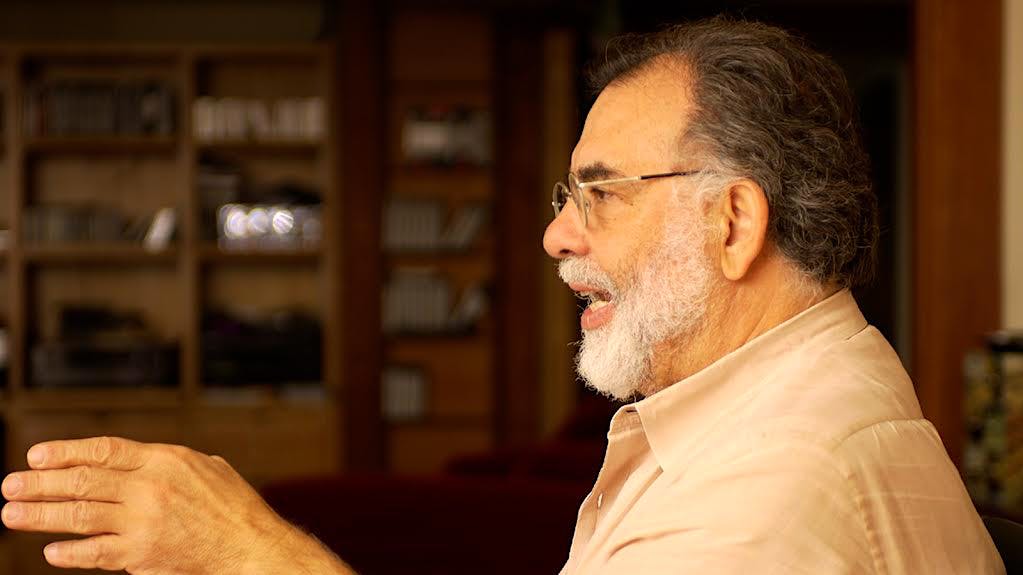

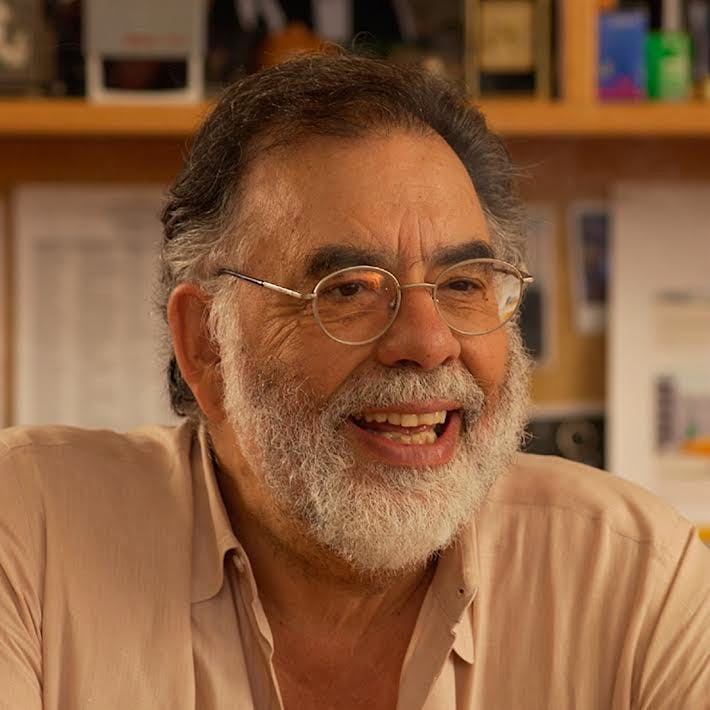

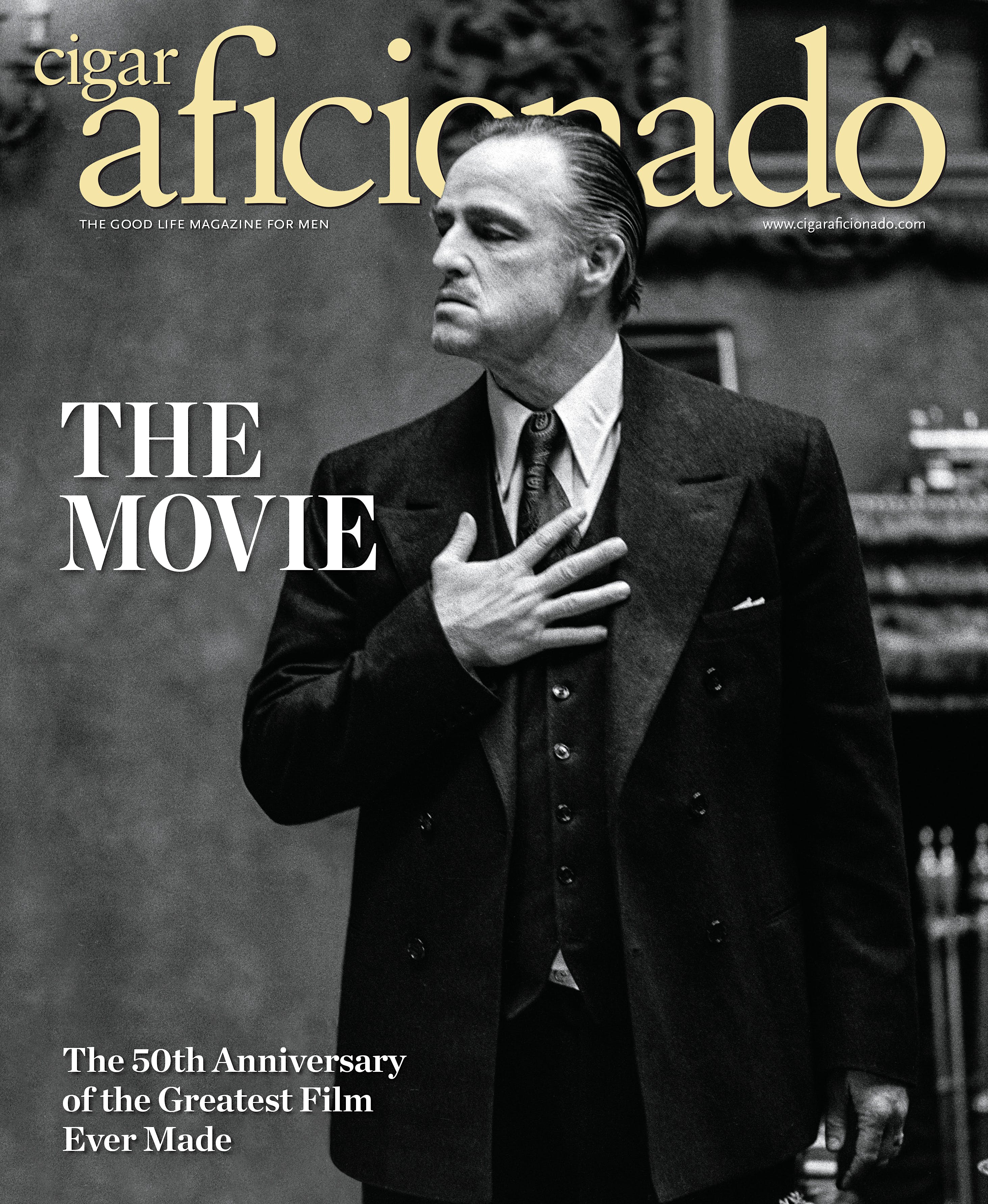

Many people consider The Godfather to be the greatest film ever made, and the March/April 2022 Cigar Aficionado celebrates its 50th anniversary with a comprehensive cover package that goes into the making of the movie, and the reasons for its enduring appeal. Back in 2003, editor and publisher Marvin R. Shanken sat down with the man who made the film, director Francis Ford Coppola, for a long interview that discussed the creation of the movie in incredible detail. Excerpts of that interview appear in the new magazine, but the entire interview is presented here on our website, with an array of photographs from the long conversation, and many of them have never appeared in Cigar Aficionado. Read this piece to get insights from the man behind The Godfather and discover things you never knew about this amazing, classic saga.

Francis Ford Coppola is one of America's greatest movie directors. Ever. He has been associated with some of the most compelling films of the late twentieth century, from Apocalypse Now to The Conversation to The Godfather I, II and III. Those films have earned him a place in the pantheon of filmmaking.

It wasn't always that way. He struggled after his graduation from film school, earning his living as a scriptwriter and making small-budget movies that never hit it big. He took an entourage of talented young filmmakers, including George Lucas, and headed to San Francisco to escape the studios' big-business apparatus in Los Angeles, and to give free rein to the group's creativity.

The struggles continued there. But one day in the early 1970s, the offer came to direct a movie based on Mario Puzo's then unknown new book, The Godfather, a sweeping history of a Mafia family in New York. Coppola wasn't initially interested; he wanted to make the film that would eventually be called The Conversation. Lucas was almost apoplectic; the company that Coppola had formed, American Zoetrope, was broke. The filmmakers were broke. And the offer from Paramount Pictures to direct looked like the financial bridge that could keep the group going. In the end, Coppola agreed to take on the project, but that was just the beginning of the difficulties.

In an unusually candid interview with Marvin R. Shanken, the editor and publisher of Cigar Aficionado, Coppola pulls back the curtain on a storied chapter of American moviemaking history. He talks about the negotiations, the fights and the inner power struggles that surrounded the making of The Godfather. And, he speculates about why the movie has become one of America's favorites.

Cigar Aficionado: The Godfather is frequently named as America's favorite movie. But there are reports that Paramount offered the film to as many as 30 other directors before you, and they all turned it down. What's the background of how you got involved with The Godfather project?

Coppola: I don't know if 30 directors turned down The Godfather, but definitely some directors did. There had been a movie a year or so before The Godfather based on a novel called The Brotherhood, starring Kirk Douglas. It was a big studio production, sort of about the Mafia. It was not successful. When The Godfather proposition came out, a lot people thought, "That won't work."

Hollywood is very quick to judge what can work and what can't work. So, the idea didn't really light a fire with anyone. The movie studio executives concluded, when Puzo's book first came out, that they would make a movie very cheap and they would get a young guy who knew about the new cost-conscious techniques.

In those days, directors were all pretty much more mature men, part of that directors' club in Hollywood. No film student had ever made a feature film. I was 29 at the time. The idea was to make the film for $2 million or under, and maybe hire a director who is Italian or Italian-American so they might understand some of the family relationships in the film.

At that time, I was the first film student who had ever gotten the chance to direct a feature film. I had a modest little success in New York called You're a Big Boy Now and there was lots of talk in the movie industry about new equipment, new lightweight, lower-cost methods. The studio—Charlie Bluhdorn's Paramount Pictures—was interested in making a very inexpensive version of the book.

There's a story I love to tell about this movie, because it's a true story. It's really sort of uncanny. All my film school buddies and I had moved to San Francisco to try to be independent. We wanted to make personal films more like those art films in the '50s, like The European. I had a young, oh, call him a protégé, a guy named George Lucas. He was five years younger than me and was a film student. I was the only one who had any money because I had had a successful screenwriting career for about three years. I had a house. I had a summer house. I had a Jaguar. I had a couple of bucks.

I sold everything to put together this little bit of money, and we moved to San Francisco. We started an independent company, which we called American Zoetrope. One Sunday, I got a call from a guy named Al Ruddy and his partner named Gray Frederickson. These guys said, "We're up here making a film with Robert Redford called Little Fauss and Big Halsy and we want to come see you." The Sunday Times had just come and, as I was looking through it before they got to my house, I noticed a little ad in the book review. It was this stark hand and strings of a puppeteer and it said "Mario Puzo's The Godfather." I was drawn to it because I thought that sounds like some intellectual Italian writer, Mario Puzo. It was maybe like another Italo Calvino.

I was looking at the ad and wondering, who is this Mario Puzo? Is that an Italian writer? I had no idea. The book looked like it was about power. I was attracted to it. While I'm looking at it, the doorbell rings and these two guys who were making the Redford film come in.

I was trying to make a movie at that time, a more personal film called The Conversation. I had sent the script to Marlon Brando, whom I didn't know at all. But I greatly admired and looked up to him. I'm looking at The Godfather ad, and I'm talking to these two guys who are making a film with Redford, and the phone rings. I answer the phone, and it's Marlon Brando.

I hear the voice. I recognize it. He said [mimicking Brando's voice], "This is Marlon Brando." I said, "Gee, Mr. Brando," "I read your script," he says. "I think it's very good. It's not for me." And I said, "I thought it could be an interesting character, you're a wiretapper." "You know, I thought it was good, but it's just that I'm not interested." I hung up the phone and I said, "My God! That was Marlon Brando."

It's very interesting that on that same day, without anyone knowing it, that Al Ruddy and Gray Frederickson would later be given this Godfather book, become the producers, and make the film. I had noted the ad for the book. And while Ruddy and Frederickson were in my house, Marlon Brando called me up. What a kind of cosmic thing is that, that on that one day all the pieces that were later to become The Godfather, came together. No one knew it. Brando didn't know he was going to be in it, Ruddy didn't know he was going to do it, I didn't know I was going to do it. They all came together on that same day.

A few months later, we're broke. We're so broke, the sheriff is going to chain up our offices because we haven't paid taxes. George Lucas is a worrywart. He's saying, "Francis, we gotta make some money. Whatta we gonna do?"

For some reason, Paramount offers me the opportunity to direct this book The Godfather, and they say Al Ruddy is going to produce it. And I said, "Wow," and George is saying, "Do it." I said, "But, I wanna do The Conversation." He says, "Well, we gotta get some money." So, I read Puzo's book. If you remember the original book, it's not by some intellectual Italian writer; it's like some guy in Brooklyn or Bay Shore, who's Italian-American. I thought, when I read the book, that the story of the brothers and the father and the Mafia was interesting. But it was also, if you remember, a book about this girl who has extremely large genitalia. She had an operation and the doctor who fixes her body is the first to sleep with her. It's all kind of sleazy. So I turned it down.

George Lucas is having a fit. "Francis," he says, "don't turn it down. We are broke. We're out of business. We're closed." And I said, "But, gee, George, I wanna make The Conversation and, you know, the book is so sleazy." He says, "Well, find something in it that you like." So, I remember going to the public library and looking in the library shelves about the Mafia.

CA: Am I right to assume, then, that you knew nothing about the Mafia?

Coppola: Nothing. All I knew about the Mafia is that there had been a movie called Black Hand, starring Gene Kelly, that I had seen when I was a kid. My father took me to see it. And I knew there was something about the Mafia, but I knew nothing about what it was or how it worked.

I had made my success writing war movies: Patton and stuff like that. But they hadn't come out yet, so in reality, I had no success. I remember going to the library and I pulled out three books on that subject. I read them all.

CA: Do you remember the books?

Coppola: They're the old classic books, and they talked all about the so-called New York families and the famous turning point in the New York Mafia history—the murder of Mafia chieftain Salvatore Maranzano by Lucky Luciano. Luciano emerged at that time. And then it talked about Vito Genovese and Joseph Profaci and Joe Bonanno. And it was a book all about connections and lives.

I was fascinated by this whole idea that there were these various families that had divided up New York and they ran them like businesses. One would take drugs and one would take prostitution and they were all in the businesses that were made illegal by our laws. But people like to gamble and like to go to prostitutes and like to do drugs and stuff like that.

When I read those books, I turned around my attitude. I said this Mafia stuff is really quite interesting. I'd heard of Lucky Luciano, but he was fascinating. And then my memory came back to me. There was a very famous Mafia guy in New York. His name was "Trigger" Mike Coppola, same spelling.

CA: Obviously, a relative [laughs].

Coppola: No, he wasn't related. But I remember my Uncle Mikey and my father talking and making jokes, "Oh, we're gonna go see 'Trigger' Mike." Well, one of the things about "Trigger" Mike was that in the '30s or '40s he had married a burlesque dancer. I think her name was Doris. She browbeat him constantly and he was always in a fuss over his wife. My father and my Uncle Mikey ridiculed him. I also had an Uncle Dante, who I think knew these kinds of Mafia types. He was a very beloved uncle. So, it all started to come back to me, the family talking about this stuff and particularly this "Trigger" Mike Coppola.

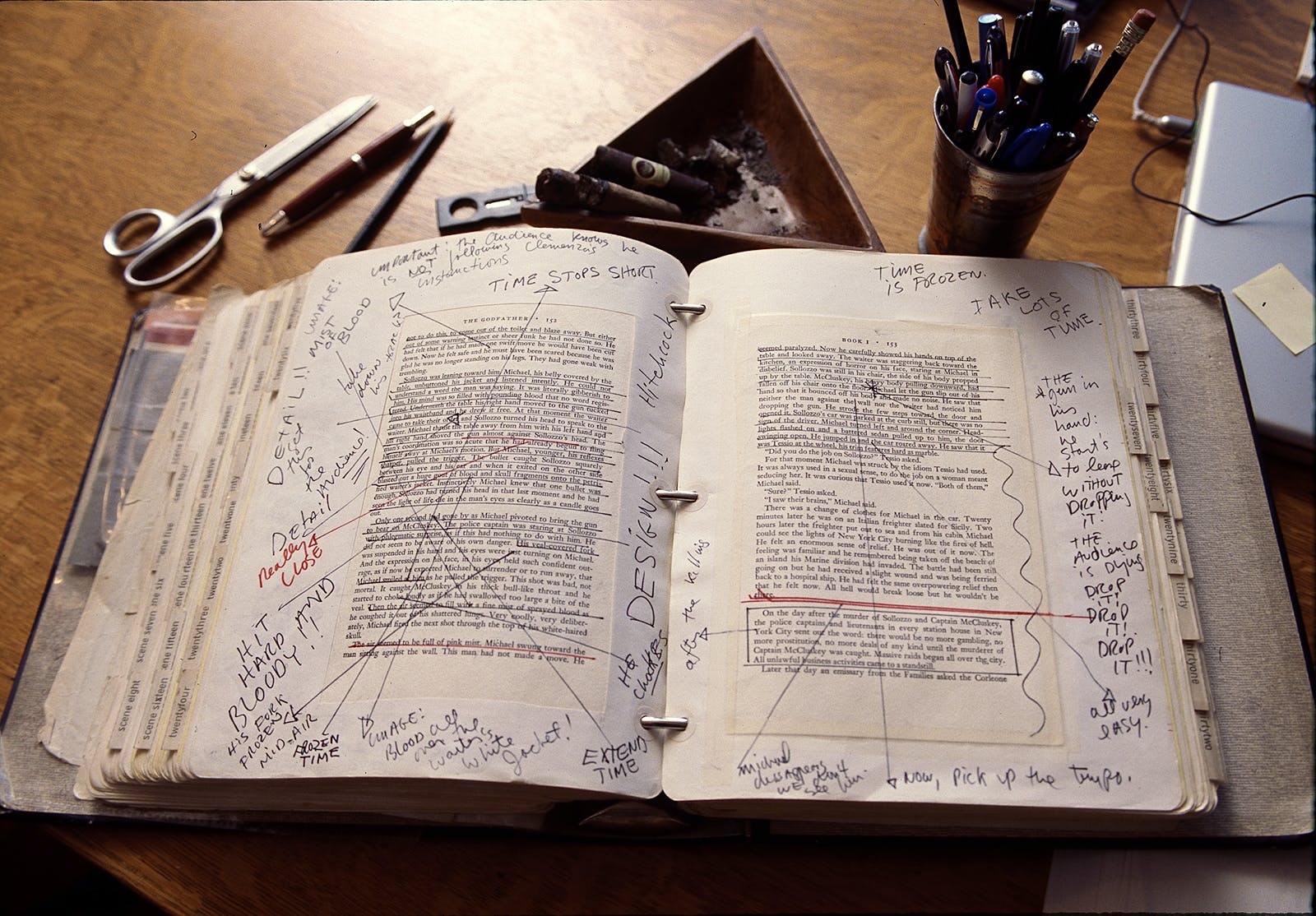

Having finished the books, I had new reference points. So I went and I read The Godfather again. And this is the actual book that I read. [He holds up a book.] When I read it, instead of just reading it, I underlined everything and made notes as to everything that I thought.

In other words, this book is the first book of The Godfather, the movie. I cut it up, with all my notes on it, and I put it in a big loose-leaf binder. I begin to diagram the story and write down the theme for each scene, what the family relationship was all about in that scene. I analyzed the entire book like this.

CA: What percentage of the movie comes from the actual book, and how much did you improvise and make up?

Coppola: When I directed The Godfather, I didn't use the book or the script I had written. I used this [referring to the loose-leaf binder with diagrams]. I broke down each sequence, I made a little synopsis as to what happens, I wrote a paragraph as to what the time period, the 1940s, was like. Then, I put in images and the tone for each scene.

CA: How much time did you spend preparing for the movie?

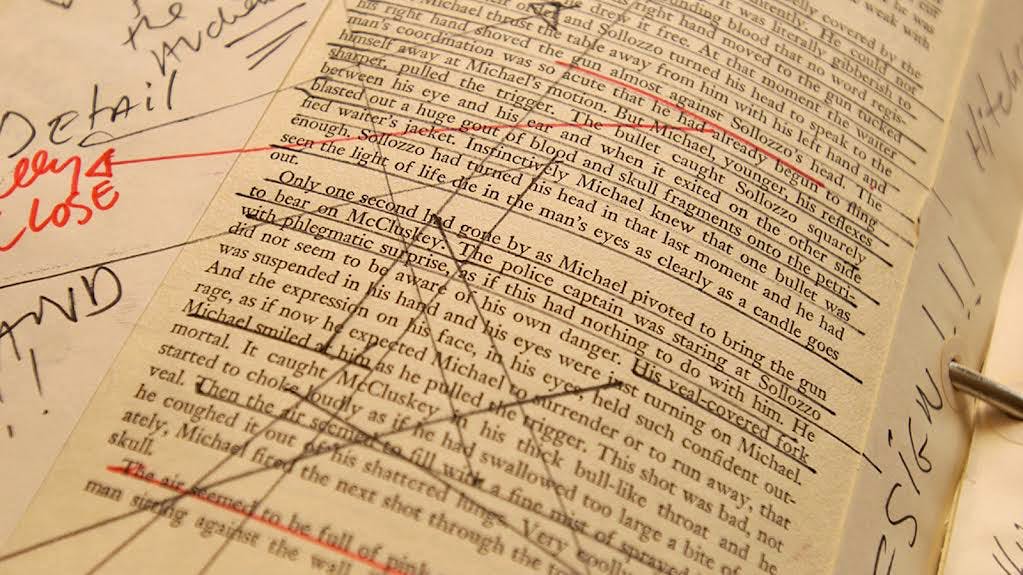

Coppola: Well, in truth, I read the books and I made the notes and then I took the job. When I accepted the job, I cut all the pages out of the book where I made my notes, and I glued them into this thing myself. I made this myself. And then I went through very carefully and I analyzed each scene. Like this. This was the scene when Michael killed Sollozzo in the Italian restaurant.

CA: Oh, I remember that, the one where Michael gets the gun out of the men's room. That was quite a memorable scene.

Coppola: This book was done months before the filming. There was no movie at this point. But I had the job. And then I used this book to write the script for Paramount, [production head] Robert Evans and those guys, and I turned in the script. I had decided that the book had a jewel in it, which was the story of the father and the three sons.

CA: When did you realize that The Godfather had captured a mass audience?

Coppola: The answer to that question is after the movie. The movie was a black sheep at Paramount. They didn't like it. They didn't like my idea. They didn't like me.

CA: But I've read articles that Charlie Bluhdorn was behind the picture, and that because you were an Italian, and only an Italian could do this movie, [the studio was] behind you, too. Is that true?

Coppola: They were behind it. That was as much Bob Evans and Peter Bart [Paramount Studios' vice president of creative affairs] as Bluhdorn. But at the beginning, they felt that by getting a young Italian guy, (a) they could make the movie cheap, (b) they could boss him around, and (c) it would give it some Italian flavor.

You gotta realize the budget was a little under $2 million. It was a book that was starting to attract attention, but the book had not become a success yet.

CA: How much did the movie end up costing?

Coppola: $6 million.

CA: That's all?

Coppola: Yeah. $6.2 million.

CA: You couldn't bake a cake in Hollywood today for $6 million.

Coppola: Yeah, but in those days, $6 million was more than just tuna. It still is. I'm gonna try to place this in a time frame for you. I wrote the script. At this point, it's a little movie. They are hiring a cheap, low-budget director who was supposedly gonna be able to make the film cheap and they could push it out the door. They showed me a script that Mario Puzo had written under their supervision that I hated. First of all, it was set in 1972.

CA: The movie was released in 1972, right?

Coppola: Yes. The original script was set all in contemporary time. It had hippies in it. That's because a contemporary movie is much cheaper to make than a period movie. For a contemporary movie, you go out in the street. The clothes are the same, and the hippies are right there.

I went to them and said, "I don't want to make it as a contemporary movie. I think it's very important that this movie is also about America. And I think it's very important, like the book, that it should be set in the '40s." "Absolutely not," they say. "Absolutely not. If we set it in the '40s, we're gonna have to have costumes, we're gonna have to have sets. Cars. We gotta get old cars. We gotta make the budget, so absolutely not." I said, "Well, to me, the story won't work with hippies in it. It's a classic story," I kept saying.

I had decided I wanted to focus on the story of the father and the brothers. Forget all this other stuff, I was saying, and do it like a classic story. Like a Shakespeare story. Tell the story about the man, and he has got to find a successor. He's got one son who's tough and a Mafia guy. He's got one son who's sort of a little bit light-headed. He's got a third son, his youngest son, whom he probably loves the most, who is a war hero and he wants to go into politics and not be dirty. And I said that's what the movie's about.

Then I hit them with the really tough one; I had to make the movie in New York. "Absolutely not. You're crazy, you can't make the movie in New York," they said, "And you want to make it 'period,' you're not going to make it 'period,' you're going to make it in the '70s as cheap and you're not gonna make it in New York." I said, "Well, where am I gonna make it?" The studio guys say, "Well, you're gonna make it in L.A. or you're gonna make it in Kansas City or you're gonna make it in San Francisco. It's not gonna be in New York. New York is the most expensive place in the world to shoot a movie. You cannot make it in New York."

I'm just a kid. I'm 29 years old. I have no money. Meanwhile, as this is going on, Marvin, the book is becoming a best-seller. They're looking at this book, which they thought would make a cheap movie. The book has been selling and selling and selling and they're starting to say, "Hey, get rid of this kid. This is a big best-seller. He's not even very good; he's not cooperating and he's got terrible ideas. He wants to make a "period" movie. He wants to make it in New York."

I say, "OK, let me consider making it in Kansas City." [Along with] Al Ruddy and Frederickson, these two guys that I had set up as producers, we go look at Kansas City. We go to the Italian neighborhood in Kansas City. We go look around in San Francisco. And I said, "I don't care. This movie has to be made in New York. It's a New York story. It's the five families of New York, for God's sake. What do we do? Make it in Kansas City? And it has to be 'period.' "

Now I realize that they're starting to go out to more important directors to see if maybe they can get rid of me, who's making trouble. The budget is not going to be under $2 million if he makes it in New York. I heard rumors that they had offered it to Costa-Gavras and then Elia Kazan. They both turned it down. People were turning it down because that movie The Brotherhood had been a flop and no one saw any potential.

I was hooked now on what I had read during my research. When I read about Vito Genovese, I began to see how Mario had taken the real guys and combined them. Vito Corleone was really a combination of Vito Genovese and Joe Profaci. I began to see that, in his own way, in his fictional way, he was using the real stories of famous Mafia murders and these various gangland wars that were going on.

Then trouble really started to happen. I'm trying to figure out ways to make it in New York and keep it on the cheap. Then, we start talking about casting. I need to place this in perspective, because the rumblings didn't start right away. They were still pissed off about the fact that it was "period" and that meant it couldn't be made for under $2 million.

I started interviewing people. There was a photographer I had heard of that had never done a lot of motion pictures but that I thought was very talented. I started interviewing art directors and costume designers. I began to choose the people that I wanted to meet and I deliberately chose people who were based in New York. I figured that they'd say, "Oh, my God," you know, "we got the guy who lives in New York. If he had to make a trip to Kansas City, we're gonna have to pay his travel and expenses."

I was already pushing the issues. Then, we start talking about casting. Their first idea for casting was, "What about [Robert] Redford for Michael Corleone?" I said, "Well, Redford's a very bright guy and wonderful, I think, but, he doesn't look Italian." They said, "Well, Italian…there's a lot of Italian blonds. Sicilians are blond and have red hair and blue eyes." I says, "Yeah, but don't you think that Michael, the son that is not gonna go into the family business, ought to look Italian so it's like he can't escape his destiny? You know, if he's blond, he'll become Robert Redford, he will be a Wasp banker."

Then they suggested Ryan O'Neal, because he had just had a big hit called Love Story. They really thought Ryan O'Neal was a good compromise because he was younger and had become a big star. Ryan O'Neal, and Ernest Borgnine as the father. So, they're starting to cast it. As I said, one of the reasons I got the job is because they thought they could push me around.

I said, "I don't know yet who can play The Godfather, but there's a young actor that I know. He has never been in a movie, but every time I read the scenes with Michael Corleone in the book, like him walking in Sicily with the two bodyguards and the girl, I kept seeing his face. And when I read it, that's the only one whose face I saw." Evans said, "What's his name?" I said, "Al Pacino." He said, "Well, who is he?" I said, "Well, he's a theater actor, but he's never been in a [film]." So, they did some research and Evans said to me, "A runt will not play Michael." I said, "What d'ya mean, 'a runt'?" He said, "He's a little short guy." I said, "Well, yeah, but he's a good actor, he looks Italian and he has power and I think he should play that." "Absolutely not," was the reply. "Michael Corleone will not be played by Al Pacino. You will not have Al Pacino in this movie and you will not shoot it in New York and you will not make it 'period.' "

I was very disappointed because I was sure that this young actor was really great; and I couldn't convince them. I couldn't get any support. So then they said, "Well, what else, who else do you have?" I said, "Well, we could just go look at all the young best actors and actresses. Let me…give me a little time and I'll do it."

I had worked with a guy named Bobby Duvall on two or three pictures. I worked with a wonderful casting person named Fred Roos. So, we worked together and we started to figure out, what if Pacino plays this part? I got all of the other actors to come up to San Francisco. They were all sort of old friends and all unknowns. My wife cut their hair and got some clothes and we shot on 16mm film a whole bunch of tests of scenes.

You can see these, they're really funny—of Pacino playing the guy. Jimmy Caan. Diane Keaton was a kind of quirky actress. But I thought the part of Kay in the book was so strange that we needed a real Wasp, but also an actress with the personality and someone a little quirky who could play Kay.

They all come up to San Francisco. We're all living in my house. My wife, Eleanor, is putting their clothes on. And we're shooting all these tests. We sent them down to Los Angeles. That's when the Paramount guys really started thinking about firing me because I have spent maybe $500 for meals and other stuff. But I gave them all these screen tests and they said, "Listen, Francis, we're taking over. You have to really cast this movie. Don't give us this Al Pacino and all these people like Bobby Duvall, we don't want them."

They made me go into a very intensive screen test mode. We had to test every young actor for every part and shoot it on film, and so we tested everybody. We tested Martin Sheen as Michael. Dean Stockwell as Michael. Ryan O'Neal as Michael. There were hundreds of tests, and we spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on them. But then, we went back to my $500 worth of tests, and they finally look at these tests and they are totally dismayed.

Bluhdorn, in that German or Yiddish accent he had, says, "I look at all these actors and they're all terrible. Let me ask you: Is it logical that every actor we test is terrible? No. The director is terrible. There are 15 actors and there's one director. If the director's terrible, get rid of the director."

They didn't want my suggestions and they didn't even want me. They're offering the film to another director. I keep saying, "No. I feel that the movie has to be cast this way." Ultimately, they said, "What about The Godfather?" I said, "Well, lookit, there's no old Italian guy." They said, "What about Carlo Ponti?"

Evans had a great idea. "Let's get Carlo Ponti to play The Godfather. He's a real Italian guy. He's not an actor, but he's been around show biz." I said, "But gee, Carlo Ponti's a real Italian. He speaks English with an Italian accent. New York Mafia guys are not Italian. They're New Yorkers. They speak like New York people." I knew all my relatives—my Uncle Mikey, my Uncle Danny, probably "Trigger" Mike Coppola—they didn't speak like this: "I'mah gonna tell you something." They spoke like they speak in "The Sopranos."

I said, "I don't want a real Italian for the part of The Godfather." I wanted either an Italian-American or an actor who's so great that he can portray an Italian-American. So, they said, "Who do you suggest?" I said, "Lookit, I don't know, but who are the two greatest actors in the world? Laurence Olivier and Marlon Brando." Well, Laurence Olivier is English. He looked just like Vito Genovese. His face is great. I said, "I could see Olivier playing the guy, and putting it on." [And] Brando is my hero of heroes. I'd do anything to just meet him. But, he's 47, he's a young, good-looking guy." So, we first inquired about Olivier and they said, "Olivier is not taking any jobs. He's very sick. He's gonna die soon and he's not interested." So, I said, "Why don't we reach out for Brando?"

I go to another meeting and the Paramount guys are saying, "Forget these other actors, because you're not going to have your actors. We like Ryan O'Neal. But, who do you have in mind for the part of Vito Corleone?" I said, "Well, I think the best bet would be Marlon Brando." "What! Are you crazy? Marlon Brando was just in a movie called Burn. If he wasn't in the movie, it would have done better. If you hire Marlon Brando, not only are you not getting any value, but you're gonna keep wanting him to stay away from the set."

One of the Paramount Pictures execs in those days was a guy named Frank Yablans. He was already working on Charlie to take over and be the big shot. He was on the East Coast and he had Charlie all ready to go with his plan; he was the head of distribution. He said "Charlie, this Brando idea is ridiculous. First of all, he's not Italian and he doesn't look Italian. Second of all, if he comes on the production, you're gonna end up just having cost overruns because he's such a pain in the neck. You get no value at all, because people will stay away. From the last picture, they stayed away from him. He's washed up, he's finished."

They called me into a meeting. I'm sitting at a table like this with all the big shots. The president of the company then was a guy named Stanley Jaffe. So, Stanley Jaffe looks at me. You know how they are sometimes. They gang up. This was the exact line: he says, "As the president of Paramount Pictures, I want to inform you that Marlon Brando will never appear in this motion picture and I instruct you not to pursue the idea anymore." So, I'm sitting like this. I fall on the floor like this [he falls on the floor] and I say, "I give up."

I did it as a gag. I wanted to demonstrate. I knew the floor was carpeted, so it wouldn't hurt. I said, "I give up. You hired me; I'm supposed to be the director. Every idea I have you don't want me to talk about. Now you're instructing me that I can't even pursue the idea. At least let me pursue it." They said, "All right."

They went and talked and decided. "We'll give you three rules, if you want to pursue Brando: One, he has to do the film for nothing; two, he has to put up a bond, a cash bond, that if he causes any more overages, the bond will pay it; and three, he has to do a screen test. He gets nothing, he's gotta put up a bond and do the screen test." I said, "Yes. I agree." I figure, what can I lose? They just told me under no circumstances would he be in the picture. Now, they're telling me these things. So, I said, "I accept."

I was thinking, How am I gonna handle this, and I knew the key thing was the screen test. I call up Brando. I say, "Mr. Brando. Don't you think it would be a good idea if we fooled around a little bit, and do a little improvisation for this role, and see what it would be like." I didn't say it was a screen test. I said it was like a little experiment with a video camera. He said, "OK." We make a date that I should go to Brando's house to meet him and do whatever we discussed.

I had done some reading about Brando. I told my crew, "You know, Brando is very much a person who doesn't like loud noises. He doesn't like all that noise and shouting and stuff. And that's why he wears earplugs a lot when he goes on the set. Let's just dress in black and let's go to his house, but no one say a word. No noise. No nothing. And we'll just communicate with hand signals. And I'll lead him through some things and you get it on film." And I had a little video camera that in those days was just starting to come out. We go to Los Angeles. We knock on the door at seven in the morning and some little old lady lets us in.

Meanwhile, I had brought a lot of stuff with me. I brought Italian cigars; I brought some provolone cheese and salami; a little bottle of anisette. All the props that I knew Italian guys had, and I put them around his living room. We all got nervous because we hear he's waking up. He wakes up. He comes out of the room. He's got long, flowing blond hair and a ponytail, very handsome. He's obviously a young man. He's in a Japanese robe. And I said, "Well, good morning, Mr. Brando." He sees what I put around, little cheeses and stuff and he sits down and he starts going, "Mmm, mmm [mumbling in the manner of Brando]." He takes the cigar and "Mmm, mmm [more mumbling]," just like that. He takes the cheese: "Mmm."

Then he goes and he takes the blond ponytail and he rolls it up and he takes some shoe polish and—this exists on film—he paints it black. I'm shooting it. He goes with his collar of his shirt and he goes, 'Those guys, they always have the collar, it's always wrinkled." And he goes like that, and he gets it wrinkled.

Now he's starting to turn into the character and puts the jacket on. He takes the little cigar and starts to light it. Then the phone rings in his house and he goes to the phone and he's mumbling into it, and I'm wondering, Who the hell was that on the phone? Then, it was over. "Thank you very much," and we were done and we leave. We look at it and it's a miracle, how he goes from this 47-year-old surfer guy into the beginnings of this character.

I got the tape. It was great. What do I do? I go to New York on my own and I go straight to Gulf & Western and straight to Charlie Bluhdorn's office, because I figure these guys are all afraid of Charlie Bluhdorn. As long as Charlie Bluhdorn is the one who's saying "no Brando," it's never gonna happen.

On a table in a conference room next to his office I set up the video recorder. I get it up to the place where Brando comes out of the room with the blond hair. I knock on the door and I go in and I say, "Mr. Bluhdorn, could I just show you something?" "Hi, Francis, whatta ya got there?" "Just come here and let me show you something." So he comes out and I flick on the tape recorder and he sees Brando on the screen coming out, so he knows I'm showing him Brando. Here's Brando coming out with the blond hair. He says, "No. Absolutely not. Absolutely not." And, as the tape is going, Brando's putting the hair up and turning…and Bluhdorn looks and he says, "That's incredible."

The word goes back to Los Angeles that Charlie thinks the screen test of Brando is incredible. I jumped over five guys that way and then the next step was OK'd. By the time they then thought it was incredible, the question is, What about the other two parts of the deal? They're not going to pay him any money, but they're gonna give him actor's scale, and then the issue of him putting up a bond all evaporated. I got them to agree.

CA: How did you get Brando to do it basically for nothing?

Coppola: Because he was washed up. His last picture was such a disaster that nobody wanted him. He didn't work for free, but he got like $300,000, which he resented greatly. Because he had no percentage.

The studio even lied to me what my fee was. When they offered me my deal, they offered me two deals: One was $125,000 and 10 percent of the profits, or $175,000 and 6 percent of the profits. So, I had no money. I mean, I had kids. So, I had to take the $175,000. So, I said, "OK, I'll do it for $175,000 and 7 percent of the picture, because seven is my lucky number. I was born April 7, I have to have 7 percent." And they said to me, Yablans said, "Sure, OK, 7 percent," but they never gave it to me. They gave me 6 percent. So I had 6 percent of the picture and $175,000.

CA: How long did it take from the day you agreed to do the movie until it was completed and in the can?

Coppola: Close to two years.

CA: So, $175,000 for two years.

Coppola: Yeah. Plus 6 percent. I wanted the 10 percent. I always would take less money up front, but I couldn't afford to. I didn't even know I was in debt. At any rate, that was the deal.

The next thing was, of course, all these other parts: Al Pacino, Bobby Duvall, Jimmy Caan. I kept fighting for my cast. I finally realized why they didn't want Pacino, why they wanted Ryan O'Neal. Bob Evans wanted a Michael who looked like him. Someone who was handsome and tall. And I wanted a Michael who was more like me, who was more ethnic. At any rate, we went back and forth, and it got to be really hot and heavy. It reached the point where they were really gonna get rid of me.

CA: It sounds like a hopeless situation for you at this time.

Coppola: At one point, I started to say, "Well, I'm gonna get fired anyway." For instance, my sister wanted to play the sister in The Godfather and I thought she was too pretty for the role. I mean, this is the Mafia. She only gets married because she's the guy's daughter. Anybody would want to marry you if you're the big boss's daughter. But Evans liked Talia [Shire]. Evans saw something in Tallie. So, when I heard that Evans liked Tallie, I said, "Let Tallie have the part, because I'm gonna get fired anyway."

Then, there was something where they all said, "What if Jimmy Caan plays Michael?" Pacino had done tests, but whatever I did they hated. Pacino takes another job. He signs for a picture called The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight. So, I lose Pacino. I go to London, because Brando is working on a picture over in London and I had to talk to him about the part. I had a nice little meeting with Brando. When I came back, I call my secretary from the airport, and I just get a message: "Don't quit. Let them fire you." So, I immediately knew what that meant. If I quit, I wouldn't get the $175,000, but if they fired me, I would get it.

It was my lawyers. They were afraid that I was gonna get so angry about them insisting that Jimmy Caan plays Michael, that it was better that I was going to go to the meeting where they were gonna fire me. I started thinking, so I'll get the $175,000 and I'll be done with this mess and I'll just go and make my own personal film. And I was totally sure that I was gonna get fired. But, I go to the meeting, and they said, "Everything's changed."

They had seen a little piece of a new movie that Pacino had done, but it hadn't come out yet. It was called The Panic in Needle Park, and they had gotten ahold of some of the scenes—and Pacino was very good in that picture—and they could see that he had something. They said, "Everything's changed. Pacino can play Michael if you'll have Jimmy Caan move over and play Sonny." I said, "Boy, I like Jimmy Caan, but Pacino's taken another job. How you gonna get him?" They had gone with their gangster connections and had a guy call up to get Pacino out of the part he had taken.

A little side story that's quite amusing is there was another actor I liked quite a bit in the screen test. His name was Bobby De Niro. But no one had ever heard of him. I thought he was incredible. I had given Bobby De Niro a part in The Godfather, of the character Paulie Gatto. So, De Niro calls me up and De Niro's not a big shot. He says, "I'm very worried, Francis." I said, "What is it?" He says, "Pacino was out of The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight and there's a chance I'm gonna get the starring part, but I don't wanna give up my part in The Godfather even though it's a smaller part, and then not get that." I said to him, "Look, don't worry. I will keep the part for you. You go out, if you get the part, great, I'll cast someone else. If you don't get it, I'll hold it for you." So, we did that.

They did get Pacino out of The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight and De Niro did get the role in that movie. Then, we're all set to go with the same cast that we had done in San Francisco for the $500 eight months before. They got exactly that cast and they didn't have to spend the $300,000 of screen tests.

We all go to New York ready to make The Godfather. I was so broke, even with $175,000 I couldn't afford anything. They give you what's called "per diem," about $1,000 a week to live on. I decided if I just banked the fee for all my debts, I could live really cheap. I borrowed my brother-in-law's one-bedroom apartment in New York that he had that was being redone. So, I had to live in there while they were painting it. I had two babies and a pregnant wife.

CA: Where was the apartment?

Coppola: It was a little studio apartment on 60th Street that was being painted. I had these two little boys and Eleanor was pregnant. We lived like real paupers. During that period, my father, who had a very tough career, was on the verge of becoming a high school teacher. He had the idea that he could write all these little dances and stuff and lead the band in the weddings. He was there, too. We're all like this impoverished Italian family. And it was just miserable. They'd pick me up every day in a station wagon with five other guys, and I started shooting and, of course, the result is I remember every day what I shot the first week.

CA: Where was the actual shooting done in New York?

Coppola: We shot on different locations. The first shot we did was the scene where Michael and Kay come out of Best's department store. And Bobby Duvall is in front of a toy store where they snatch him. Then we shot the restaurant scene where Michael killed Sollozzo, the third day of the shooting.

CA: Was that downtown?

Coppola: That was in the Bronx. It was in an Italian restaurant in the Bronx. And then the last day, Friday, was in the hospital where they go to kill The Godfather. They look at the footage, they hate it: it's too dark, the camera never moves.

CA: "They." You mean the Paramount executives?

Coppola: Bob Evans. They send this horrible guy to be my minder. This real mean guy.

CA: What's a minder?

Coppola: A minder like in Iraq. Everything I did he was there, countermanding my orders. They were convinced that this was the worst picture ever made, that I'm the worst director ever. They hated it. And it's interesting, because I've heard them on the record saying, "Well, yes, at first it didn't look that good."

But the truth of the matter, it's probably the best scene in the picture, which was Michael and Sollozzo in the restaurant. That was all shot that first week. And they didn't like it. I was being told, "Listen, they're gonna go to Kazan now, because Kazan knows Brando and they're gonna offer him a lot of money and you're gonna be out." I was always being told, "You're out."

CA: Was this common in those days? Were directors replaced all the time, or was this a very unusual situation?

Coppola: Well, directors could be replaced, especially when they're unemployed directors, as I was before the film started, and especially since I was such a kid.

CA: How old were you?

Coppola: I was 30. The last day on that first week, Friday, Pacino twists his ankle and they had to take him to the hospital and I didn't finish the scene. Now they're saying, "He's falling behind schedule." I said, "What does that have to do with whether they take the actor away with a twisted ankle?" They really were pushing to get rid of me.

I would go home on the weekend and I had to rewrite scenes and I was in a cold sweat. I couldn't sleep at night. I'm in this horrible little apartment, with all the painting, my little boys. The second week was coming up and there were a few days when Brando was gonna have his first day on set and we're shooting downtown. They're all very anxious to see the Brando stuff.

CA: So, by that point, you're saying they were high on the idea of Brando in the film?

Coppola: Well, they kept him. They're not high on him, because I had done that trick of going straight to Bluhdorn. The first Brando stuff comes in and they hate it. They hate it. They said, "Oh, he mumbles. You can't understand him. It's too dark." Even Bluhdorn hates it. It was the scene when they're in the olive oil factory and Sollozzo comes in and they all are in a room. They just hated Brando. Now they're really serious about getting rid of me. We get through the second week and now the third week comes up and we're shooting Brando with the oranges and stuff.

We're all right outside the scene. I said to them, "Listen, it was Brando's first day. The actor's first day. First of all, I didn't think it was so bad, but Brando was a little nervous and stuff." I say, "Let me go again," I said to them, because I was right. It was right there in Chinatown and Little Italy. I was out in the street by the vegetables, and where we were shooting we'd also shot the scene they didn't like. "I'll reshoot it in a day." They said, "No." I said that's odd.

Gray Frederickson says, "Listen, this weekend they're gonna fire you." I won't get into the politics, but it was a lot of politics. My editor had sold them a bill of goods that the film wouldn't cut together and that he had directed a picture and that maybe he would be a better director. And he has a friend who was his producer, and he asked them to give this guy an assistant director's job.

Now I had a group in my own movie that was conspiring to get rid of me. My own friends! They figured I was lost. But I remember this guy, a friend that I looked up to, had a meeting with me, and he said, "Francis, face it. The acting is terrible. It's not gonna cut together. I don't know what to do. I can't put the footage together."

But I've been told that film studios never fire a director on a weekday, because if a director gets fired on a weekday, then the studio loses two days in the transition. They'll always wait till the weekend. They'll fire him after Friday, then the new director comes in and he'll be ready for Monday. So I took a real chance. I went in—and I knew who all the conspirators were; there were about 16 of them—I fired them all on Wednesday.

They were like, "What do you mean we're fired?" I said, "I'm the director. Fired. You're out." And I took my crew and I went and I reshot the Brando scene. Personally, I didn't really have to. It would be interesting today to look for the two versions, but I'm not even sure which one is in the movie.

Evans had a fit. "What are you doin'? You fired the so-and-so." I startled them, so that by the time the weekend had come, I had reshot the scene. I said, "Well, let's wait and see how it looks." So, they look at it and they say, "Well, it's much better and we don't need all the bad publicity." But I had already fired everyone anyway, and there was nothing they could do. Then I get a call from Charlie Bluhdorn, and he says, "I saw the movie scenes, and it's terrific." He said, "I want you to come to dinner with me tonight." I brought my father. And Charlie Bluhdorn takes me to the Palm Restaurant and he buys steaks and lobsters. I got his arm around me. "Ah, you're great," he says to me.

And from that moment on, he figures we're stuck with this loser. Let's at least build him up a little. They knew what they had been doing to me. They had been punishing me. We had this big dinner at the Palm steak house and suddenly, Charlie Bluhdorn is my best friend.

We continued shooting. Their guy, the minder, was still on me and we went a little over budget and they were very tough on me. For example, we're shooting the wedding scene in Staten Island. There was a scene in the script in which The Godfather is sitting in his tomatoes with his grandchild where he dies.

CA: That's a classic scene.

Coppola: Well, funny story. They cut it out. They said, "You can't shoot that scene." I said, "Look, we'll do it right where the wedding is so no one will know and I can do it in fifteen minutes." "You don't need to show him die, you just cut to the funeral and we'll know he died." I said, "But, this could be nice with the little kid. I wanna shoot it." They said, "Well, we gotta break for lunch in a half an hour; if you can get it done in a half an hour, then get it."

We had the tomatoes and they made a big stink about it because the art director had flown the tomatoes in from Chicago at a cost of $3,000 or so much a tomato. We made the tomato patch and the little kid comes on with Brando, and the little kid is scared. He doesn't want to do anything. I said, "All right, we'll just do a shot. He's a little kid, he's playing and then he goes to The Godfather, but he's afraid of The Godfather." We do two takes. We have two cameras set up, which is to say we shoot it all at once. Brando says to me, "I got an idea." So, he takes an orange and he said, "We'll just shoot because we have twelve minutes."

In the movies, if you don't break at the right time for lunch, all the crew gets a fine. So, if you miss the break, it could cost like $10,000. They were there ready with the stopwatch. They would have cut me off. Brando takes an orange in the scene and he cuts it and puts it in his mouth and he smiles at them and the little kid goes, "Ahhhh [Coppola makes a whining sound]." You know…and he goes like that, and they say, "Meal break." So, it was that close that the scene wasn't gonna get shot. But we had it. Later on, we went and we did the part where he keeled over, and I was able to piece it in. Making the movie was like that.

I hated it. I hated it, I wanted to be done with it. It was the most miserable time of my life.

CA: In retrospect, you must be greatly satisfied, like a great chef who takes different food items and blends them together into great food, or a winemaker who makes great wine. You took unknown actors, a washed-out has-been, and on top of all the battles you had to fight, created something special. How does that make you feel?

Coppola: The key thing was that book I showed you. In that preparation with all those notes, I had outlined what the movie was going to be. And I had a cast of my friends who remained a really tight little group that supported me. Even though I had all this pressure from without, and nobody liked what we were doing, I had these wonderful actors who were on my side. And, I had this concept from Mario Puzo's wonderful book. That's what guided us, too.

But I had no idea, until the movie was long finished, what had happened. The struggles went on right through the editing. They pulled the music out and said how they hated the music, or how they told me to take a half an hour out or they were gonna fire me, and that when I took the half hour out, they said, "You ruined the picture." Or they said, "We ordered a movie and you brought us a trailer," so they put the half hour back in and then they said, "Look how brilliant we are, we put that in."

To me, it was just a horrible experience. I hated it. I still hate the memory of it. I didn't even know the picture was any good until a friend of mine that I called to give me some advice looked at it and said, "This is terrific." That was Bob Towne, the writer. But at the time, I had nothing positive happening.

CA: Did any of the Paramount executives ever say anything to you in the years following the movie's success?

Coppola: They desperately tried to go back and show how really it was to their credit. Evans claimed he had saved the picture because he asked me to put back the half hour that he had told me to take out.

CA: What about Pacino, De Niro, Brando?

Coppola: Yeah, we remained close and we worked together. They went on to become movie stars. But they had never been the doubters. They were just these kids I brought in and they were hoping I wasn't gonna get fired. The group was tight and remained tight. Of course, when I made the second film, which I didn't wanna make, the rules were different. Paramount had nothing to do with it. They didn't even see the script or anything.

CA: Tell me how the rules differed between Godfather I and Godfather II.

Coppola: Godfather I was done. I vowed I wanted nothing more to do with it. I didn't ever want to see anything about the Mafia or anything about the film. Charlie Bluhdorn says, "Francis, you have the formula of Coca-Cola. You should make another Godfather." I said, "Charlie, I don't even want to hear about that. I hate The Godfather. I don't want to know anything about…." He said, "But that's Coca-Cola." So, then he asked me to make a second film and I said, "Lookit, the movie doesn't need a second film. It ends at the end. It's not like Andy Hardy or something. You could make five of them. It's a drama, and it's done." "You gotta make another Godfather," and I said, "I absolutely will not make another one."

CA: What had the movie grossed up to this point?

Coppola: I have no idea, but it was the biggest grossing picture in history at that time. It changed the way movies were shown. In the old days, a movie would come out in one theater and play. In Godfather, they brought it out in six, seven theaters and that was like, Wow! It was huge. It was the big success, bigger than Gone with the Wind—at the time. So, then they started again, but I wanted nothing to do with Evans. He had made me miserable. I was so glad that I could just be free and I wanted to make my movie The Conversation, which I was gonna make before anything else.

When The Godfather came up for the Oscars, it won Best Picture, but didn't win Best Director. I was Best Director for the Directors Guild of America, but when they announced Best Director at the Oscars, Bob Fosse won it for Cabaret, so I was a little depressed, because every young guy wants to win an Oscar. Charlie said, "Francis, you won The Bank of America award." All of a sudden, my little six percent was gonna be worth $6, $7, $8 million. I had never had two dimes to rub together in my life. Suddenly—how else can you say it—I was rich just from having that little piece.

Charlie started working on me to make another Godfather picture and I absolutely refused. He kept coming and coming. Finally I said, "I will find a young director that I think is really talented, that is every bit as good as me, and we'll have him do it, and I'll help. I'll be like a producer. But, I won't do it. I don't want to be involved with Paramount." I hated those guys. He said, "OK."

You know, a lot of business guys realize like I did that even with the terms that you agree to initially, it will all change. Four months went by and I was thinking about it, so I finally go back and I said, "I'm ready. We got an idea and I would like to suggest a director."

CA: Who is doing the screenplay for this? Who's going to write it?

Coppola: I was going to help. Me and Mario were going to help. There was no screenplay yet. There was only "What was it gonna be?" You know, the guy's dead. I go back and Evans was there and they go, "Who do you want to direct it?" I said, "Well, the guy I think who'd really do a great job is a guy named Marty Scorsese." And Evans said, "Absolutely not. He will never direct The Godfather. That is the worst idea I ever heard." I said, "Well, I can't deal with this," and so, I leave. Then, Bluhdorn says to me, "Look, you gotta do it. You're the only one who can do it. What do you want?'

And I said, "OK, first of all, I want to make my movie The Conversation, that I'm gonna do now." By then, I had gotten Gene Hackman to do it. "Second of all, I will do The Godfather—the second Godfather—but I have some conditions. One, is I want a million dollars." Some stupid amount of money that I figured they'd say, Forget about it. I didn't want to do it. I didn't know how to do it. "And, number three, Bob Evans can have nothing to do with it. He cannot…he cannot see the budget. I do it alone. I will do the whole thing, but no executives can be around. Nobody can be on the set. He cannot even see the script or see the movie until it's done. And the fourth thing I want is, I don't want to call it The Return of Michael Corleone, the way they always did it. I want to call it The Godfather: Part II.

They said, "Well, the million dollars is no problem. We can work it out with Evans, but we can't agree to calling it The Godfather: Part II." I said, "Why not?" He said, "Well, because everyone's gonna think that it's the second half of the movie they already saw. They're gonna think, "Godfather: Part II, oh, we gotta go in and go see the second half." I said, "Well, that's all right. We'll use the scene."

I didn't mention this earlier, by the way, that they had all these terrible ads for the movie, and I was the one who said, "No. I just want to use the same logo from the book, with the hands and the string." Then they had to go buy that. And, I said, "Well, we'll make it in red this time, so they'll know it's our movie." So, the big sticking point was calling it The Godfather: Part II in the ad. I was the first one ever to call a movie Part II.

CA: Did they give you a bigger percentage of the second film?

Coppola: I think I got a piece of the gross, as opposed to the net. And they told me they would let me do anything I wanted. I didn't have to show them the script. I didn't have to have any permission, and it was going to be called The Godfather: Part II. And then, I sat down and I wrote a script and I brought the script to Mario and then Mario helped me and we worked together and then we put together that movie.

CA: Was that a bigger grosser than Godfather I?

Coppola: No, it grossed less money. But it won all the Oscars and I won Best Director. It was very respected. It was the first sequel that was considered as good or better than the first movie.

CA: Given that you went into The Godfather project without any prior knowledge of the Mafia, how did you re-create a story that many people came to believe was real Mafia life? How did you do it?

Coppola: And the Mob did accept it. Although I had no experience or knowledge of the Mafia, in the end, they were just an Italian-American family. I based the film all on my uncles and my relatives. Now, they were musicians, or they were little businessmen or tool and die makers, but they were true first- and second-generation, third-generation Italian-Americans. I used my memories of what it was like in my family. How they sat around the table. How my uncles would get Chinese food. What the family dinner table was like. How my sister would serve and how the uncles would discuss world events. All I did was take another profession of Italian-Americans, which was what my family was like. In acting they call it substitution.

CA: But it was so vivid. There are so many themes and sets that seem so authentic.

Coppola: Well, of course, that's just the Italian-American heritage. There are many kinds of Italians. Today, they're politicians: Governor Mario Cuomo. You have so many Italian-Americans in every walk of life. We've been in this country in tandem with the Jewish Americans, because they came at the same time and both groups ended up primarily in New York. It's as though you were making a movie about a lot of great Jewish traditions, but you didn't know any Jewish traditions.

You use what you know and the way they talked, what the uncle was like. How the feuds started with the brother-in-law or if someone had to come from another town. All I did was apply what I knew intimately, which was my own family. All that detail, and I just said, "Oh, the gangsters were probably just like that." There were little stories I grew up with. I had one uncle who married a lady, and they said her father-in-law was sort of connected in some way. So, when the uncle's daughter's got married and there was trouble, he would threaten that he knew some people that would break his leg. Those are just stories.

CA: Did you ever have any contact with the real Mafia while you were making the movie, or afterwards?

Coppola: Mario Puzo gave me some advice when he started. He said, "Francis, when you work on this, the real Mafia guys are gonna come, and they're gonna wanna know you, and they're gonna be very nice," he says. "Don't let them in. Don't let them think that they can call you up. Don't let them think that they have your phone number. They will respect that and they will never bother you and they will never try to reach you. But, if you accept their friendship and you take the gift of cannoli and if you go out and have dinner with them, then they have access."

And I remember that, when I was a kid, they're like vampires. The vampire can't come into your house unless you invite them over the door. But, once you invite them over the door, then you're theirs. So, over the course of the film, I never wanted to know them. I never started hanging out with the big one, like Jimmy Caan.

CA: Who was that?

Coppola: Carmine Persico, I believe. That whole Mafia thing he does where he goes "badda-bing"? That was done by Jimmy Caan. In other words, in the scene—it wasn't written that way—he went right up to the guy and said "badda-bing." Jimmy should have royalty on that "badda-bing," whether or not he picked it up from the guys he was hanging out with. He did go out and would hang with them.

CA: Did you ever say to him, "What did you learn that we should use?"

Coppola: No. The way I work with actors, they are always encouraged to bring everything to it. They're free. I don't say, "OK, do the scene, and do just what's written." I say, "OK, let's do it. And they do it and they know that they're expected to take liberties. I had made another film with Jimmy when I was younger, so I was very comfortable with him. Those actors, also, are very funny. They're always joking and playing tricks on each other and goofing off, which is all day long. And that was the joy of the job. It was them.

CA: What about the scene with the horse's head? That's a classic! Is that something you made up?

Coppola: Hold…hold…hold on. Let's not discount who created The Godfather. Mario Puzo created The Godfather. Now, he didn't know a lot about Mafia people either, but he did a lot of research. He did the same thing. He was broke and he needed some money and he decided that, if he wrote this book set around the Mafia, maybe he could make some money. And, so, he wrote it.

He told me that the real person he based The Godfather on, that character with the wisdom—you know, those lines like, "Make him an offer he can't refuse," or any of those things—he said he based that kind of wisdom on his mother. He said it was his mother who said those things and had that type of personality. Mario did a lot of research. But he never had known any people in the Mafia and then he wrote a novel. He was a very imaginative man and he created the horse's head. I just did it from the book.

I'll tell you the difference between the horse-head scene in the book and the horse-head scene in the movie. You might find it interesting. In the book, the movie producer wakes up, and he looks and he sees on the post of the bed the horse's head bleeding there, and he screams. When I directed it, though—and I may have made the note there—I changed it.

CA: It's under the bed cover.

Coppola: I had him wake up and draw the sheet and see the blood and think he's been wounded. And he doesn't know: Is it his body? Has he been stabbed? And he opens the sheets and there is the horse in bed with him. So, that's the difference between the way the director did it and the way the author did it.

CA: How could the fact that certain things in the film that Mario or you had come up with became accepted years later as the way things really are, like the thing of sleeping with the fishes?

Coppola: But he had heard that. He made up the idea; as a matter of fact, you see it all the time in movies, and they put a fish in a newspaper. He had made things up. I don't know what's real and what isn't real.

CA: Stop for a second. You just said something that was profound: "I don't know what's real and what isn't real." The whole thing I'm trying to get at is that millions and millions of people, myself included, believe that the way they look, the way they talk, the way they behave—everything—was The Godfather. It was the most richly accurate, detailed examination of the Mafia that anyone had ever seen or heard.

Coppola: Well, I have to disillusion you. Knowing how the movie was made and knowing what I knew, I have to tell you that it is not the truth. We staged it. We just said, "OK, you sit here and you sit here." We used common sense and, as I said, I used things I remembered from my family. But I didn't know. I'd never been around a Mafia family. I have no idea. I just assume they're like an Italian family.

The story I wanted to tell you is that Mario used to like to gamble. So, he had a lot of cronies that would hang around him. Not so much from the Mafia, but from the gambling world. And, once we were somewhere and he had some character with him and the guy looked at me and he says, "Hey, you just remember: you didn't make him; he made you." And it was true.

CA: You made this movie without any understanding or expectation that this was something that the American moviegoer would embrace. That was 30 years ago and there seems to be an endless series of crime-related movies in the theaters, as well as on television. Now we're in the next century, the new millennium, and we have this series "The Sopranos" on HBO, and people keep describing it as the next-generation Godfather. Why do you think this topic of the Mafia is so magnetic, a subject that fascinates millions and millions of Americans?

Coppola: I can only guess and speculate. First of all, America has always had an interest in outlaws, from the days that we liked to see cowboy movies or learn about Jesse James, or when we were kids and played pirates. I think we live our lives in very repetitive, normal ways. We go to work, we're all pretty much law-abiding. There's always a romantic fascination with the idea of people who don't take those limitations and kind of do what they want.

In American culture, that was exemplified by the wild West. You had these fabulous legendary heroes that came out of maybe real, authentic people in the West. But they were romanticized. People like Jesse James or Wes Harden or Doc Holliday. They enter the mythology of the country. That was picked up by the gangster movies, because the gangster was in a funny way the urban version of the cowboy that we know.

I think people are fascinated by outlaws, because, for the most part, they are not outlaws. They can only imagine. Second, I thought that when I read The Godfather, that there was something really attractive about the idea that if you have had injustice, if your neighbor has done something terrible or someone has been unfair to you, and you know that you can't really go to the police and the legal system isn't going to honor your complaint, that there's something really attractive about the fact that you could go to someone like a godfather and say, "Lookit, you know, they've done this to me. I was innocent, they did this to me." And you would get justice.

I found that first scene in the beginning of the movie, when the little undertaker tells the story about the daughter who was raped, that you could go to someone. I think that was a very powerful idea that Mario came to understand. All of us would like that, as we're double-crossed or someone takes advantage of us. I think there is a fascination with the romantic outlaw.

That's the idea that you can get real justice from someone without going through the corruption of the court system. I think that was partly what had to do with the appeal of Mario's book, because we must remember that Mario's book was a masterful, masterful best-seller. And that the movie picked up the energy. Everyone knew The Godfather was kind of like Gone with the Wind. When I was hired, it wasn't. But, by the time a year or so had gone by, The Godfather was a phenomenon.

We made a famous movie years ago called American Graffiti and, like a year and a half later, there was a television series called "Happy Days" with Ron Howard. Television always looks to what's going on in the movies and tries to pick up and leverage that.

CA: "The Sopranos," of course, is happening 30 years later.

Coppola: There were three Godfather movies. But all these people loved to watch The Godfather and quote the lines. It became a kind of cultural phenomenon. There are three reasons that happened. One, because it had that extraordinary cast. It was a case of all the planets lining up correctly. You had a good cast, you had a wonderful book, you had a great photographer, you had a terrific art director, you had great music—you had all those things, and the public was ready for it. It's like chemistry. If you get the formula right, it will take off. It was furthered by Martin Scorsese. He made some great movies, notably Goodfellas, which looked at a more realistic view of the Mafia. My Godfather was more classical and not as gritty and as realistic as Goodfellas.

Marty was raised in Little Italy in Manhattan where there really were these fellows and they knew who they were, right in their own neighborhood. Don't forget, Joey Gallo was killed right in Umberto's Clam House, right down from where Marty was raised. Marty was a religious kid. He wanted to be a priest. He saw the Mafia from a different point of view than The Godfather. He saw it more from the little guy's perspective. He made movies more based on that perspective. And, then, what happened was "The Sopranos." But I haven't seen "The Sopranos."

CA: You've never seen the show?

Coppola: I'm so sick of the Mafia, everything about it. They just kind of picked up on what The Godfather had done and said, "Let's make a television series. We'll have a character who's one of those underbosses."

CA: So, you weren't directly or indirectly brought in as a consultant for "The Sopranos"?

Coppola: No way. I knew nothing. I don't think I've ever seen one. I do know Jim Gandolfini because I like him as an actor. He's a big interesting guy.

CA: You met him before or after he started playing in "The Sopranos"?

Coppola: I probably met him before, but didn't know him. I did meet him after the show began, too, and I spent a little time with him. I just liked him. He's a good actor. Usually, television series pick up on what happened in the movies years before and the public was still interested. The Godfather gets watched. I made The Godfather 30 years ago and they watch it as much now as they did then. So, it hasn't gone away. So, some smart guy said, "Lookit, let's have a new show. It'll be kind of that type of setting except maybe we'll do it from a lower level of the Mafia in New Jersey," or wherever it's supposed to be. It really comes down to that they wrote it well, apparently, and they have good actors. Well, I mean, movies, entertainment, theater—it's all about good acting and good writing that comes together.

The love affair with the outlaw, now in the form of the Mafia, has taken off once again. It's an extension of the same thing. Godfather still sells more now than it did when it came out.

CA: What do you mean, as a video?

Coppola: There's more every year: the DVD, the this, the that; it doesn't go away. I mean, it's like owning an apartment building and you keep getting the rent.

CA: And, it's also on TV.

Coppola: And it's on TV. I had some very low days, as you know, after I lost my studio and went through bankruptcy. It wasn't really bankruptcy, but it was a reorganization. And we lived off of The Godfather royalties and Apocalypse Now royalties.

CA: Do you ever see yourself doing a Godfather again?

Coppola: No. I personally didn't feel there was a necessity to make a second one, much less a third one. The third one I made because I was really broke.

CA: I'm fascinated that you've really never watched "The Sopranos." It's been on about four years and it's a topic of conversation no matter where you go. In some ways, one could argue that you were, in part, one of the fathers of it.

Coppola: I have an attitude about film and art. I think one of the reasons you make art is that you hope that it's going to get out there in the culture and that other people are going to take it and redo it and make it again. Young people are going to take your work and think of it in a new way and go on. In a sense, it's like having children that you love. I love the idea that my children are going to take over for me. By the same token, I like that filmmakers take what we did and remake it.

CA: In your life, you've done a lot of things. But without The Godfather, you might not be in the position to have the vineyard, the winery and the estate. Is that correct?

Coppola: I bought this place in 1975 with the money from The Godfather.

CA: What, in your mind, is the high point of your career? If not The Godfather, what was it?

Coppola: The Godfather is not the high point of my career because it was such a horrible experience and I hate the memory of it. I become nauseous when I think about it. For me, given what I want to do in my life, the high point of my career is The Conversation, because it was a film that I really wrote from scratch and I got to make the way I wanted to make.

But, I acknowledge that The Godfather is the event that made me, that put me on the map in a way so that I was able to make The Conversation and Apocalypse Now and other stuff. I am respectful of The Godfather.

First of all, movies are the work of many people, and The Godfather was the work of myself, Mario Puzo, Al Pacino, Marlon Brando, the cinematographer Gordy Willis, the art director Warren Clymer. In other words, I acknowledge that it was really a team. But all movies are. Everything you do in life is a team thing. I acknowledge that The Godfather really made me, but it also bugged me, too, because I couldn't escape it.

CA: Doesn't that always happen when you are the chef that married the ingredients?

Coppola: I was the chef. And the plan was in here, in this book. If you look at this, you'll see everything in that movie exactly the way it's done and why I did it that way. I was very fortunate that I had this recipe.

The March/April Cigar Aficionado takes a comprehensive look at the 50th anniversary of The Godfather, considered by many to be the greatest film ever made. The magazine is on newsstands now. Click here to get an issue, or for more information.