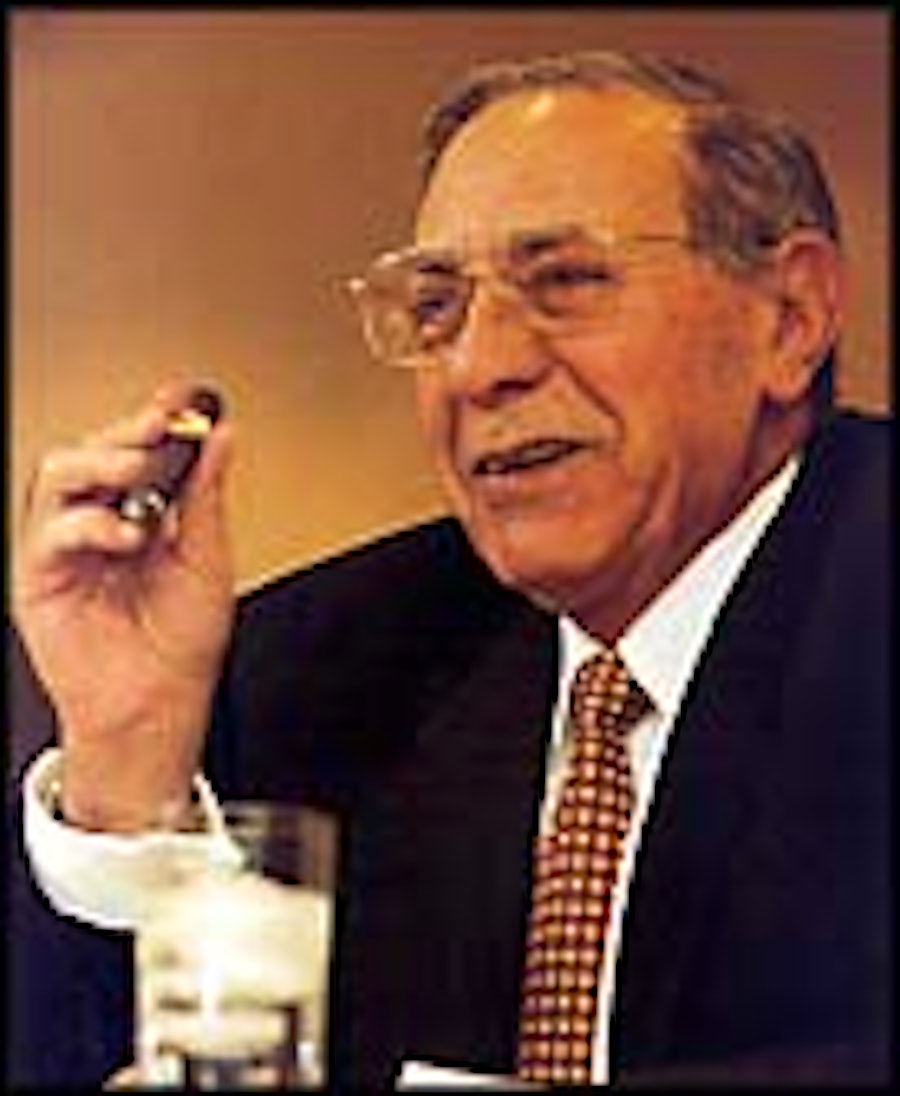

An Interview with Jose Padrón

Jose Padrón's family started growing tobacco in Cuba in the 1850s. But the Padrón legend didn't soar until more than a century later, when, after leaving Cuba in 1961, Jose Padrón began making his brand in Miami. His motivation was simple. He had grown up around the best tobacco in the world in the Pinar del Río region of Cuba, and he wanted to re-create the taste and quality of the cigars made from that tobacco.

Today, Padrón, 72, continues to make some of the finest cigars in the world as chairman of his family company, Piloto Cigars Inc. The Padrón brand has become a buzzword for connoisseurs of full-bodied smokes. While the family struggled for a number of years trying to solidify its base in Miami and then in Estelí, Nicaragua--enduring anti-Castro bombings in Miami and the Sandanista revolution in Nicaragua--the Padróns have become key figures in the resurrection of the Nicaraguan cigar industry. While most of the family's land in Nicaragua is back in production today, it still hopes to regain title to its best farms, which were taken over during the Sandinista revolution in the early 1980s.

Jose Padrón's perspective comes from the position of a man in charge of his family's destiny. His production has increased during the incredible boom in cigars during the past five years, but it's not running out of control. Padrón's policy of not rushing tobacco into production has kept growth in the brand moderate and steady. For the Padróns, quality, not quantity, is foremost.

In an interview with Marvin R. Shanken, editor and publisher of Cigar Aficionado, Jose Padrón and his son, George, company president, discuss the family's long cigar history, from their beginnings in Cuba to the company's status today.

Cigar Aficionado: When did your family start in the cigar business?

Padrón: My grandfather, Damaso Padrón, emigrated from the Canary Islands to Cuba at a very young age. It was in the mid-1800s, around 1850 or 1860. In the old days in Cuba, most of the tobacco growers [had emigrated] from the Canary Islands. They were called Isleños [the Islanders]. When they arrived they were very poor and it took much hard work to eke out a living.

CA: What did your grandfather do in the Canary Islands before moving to Cuba?

Padrón: He was very young when he came from the Canary Islands. But there was already a tradition in Cuba that Isleños worked in the tobacco farms. The Spaniards worked in the warehouses. So the Padróns started in the tobacco fields. We are talking about a time when tobacco in Cuba was sold at $7 per 100 pounds.

CA: Did your grandfather start as a field worker?

Padrón: No, the family bought a small farm with some money that they had brought with them.

CA: Where was the farm?

Padrón: Las Obas; it was one of the first farms in the Pinar del Río. But the family was very poor. There was very little money then.

CA: Did they grow wrapper or filler tobacco?

Padrón: They grew both wrapper and filler. It all depended on the quality that was being produced; much like today, really.

CA: The family started with a small farm. What happened after that?

Padrón: His sons continued the same traditions as my grandfather, and they kept buying farms. The second one was in Consolacion del Sur, also in the Pinar del Río, and then they bought another one in Piloto, which is the name we've used for our company today.

CA: So your father was a tobacco grower; did he also make cigars? Or did he just sell tobacco to cigarmakers?

Padrón: During the era of my grandfather and my father, we only handled the pre-manufacturing phase: tobacco growing, fermenting, sorting and deveining.

CA: In other words, they finished the tobacco and then shipped it somewhere else for the actual rolling.

Padrón: Yes, but we have always believed that those phases of the production process are the most important steps in making great cigars.

CA: What was your father's name?

Padrón: Francisco Padrón Blanco.

CA: Do you know that one of the top men at Habanos, the Cuban cigar monopoly, is named Francisco Padrón?

Padrón: I spoke with him in Cuba. He is also the son of an Isleño. All the Padróns of Cuba are descendants of Isleños.

CA: How old were you when you got into the tobacco farming business?

Padrón: At the age of seven, my first job was cleaning the seed beds. I went to school in the morning and then I'd come homeand clean the seed beds.

CA: What role did your family play in the tobacco world in Cuba?

Padrón: When you are involved with tobacco, it does get into your blood. Having the history of the family, my father was one of the founders of the Association of the Tobacco Growers of Cuba in 1942. After that, another association was formed that was called Caja de Estabilizacion. The group planned and controlled the amount of tobacco in production and what could be used for cigars. During the war, the demand for Cuban cigars went up, a lot like what we went through in the last five years. As a result farmers were using tobacco that would not have been used under normal conditions. The Caja imposed rules like, if the farmer had grown 10 acres the year before, he couldn't grow more than 10 the next year. They also controlled the types of tobacco that could be used. They basically controlled the quality. Before that, the system had become a mess, and everybody started to manufacture. But the new group established a system of ensuring quality.

CA: Were you living in Pinar del Río then?

Padrón: Yes, I was a child but I remember all that was goingon at the time.

CA: Did you ever stop growing tobacco in Cuba during that period before the revolution?

Padrón: No. Throughout the 1940s and '50s, we kept growing tobacco and supervising the quality of the tobacco that was being grown.

CA: What was your life like in the late '50s before Castro came in, and then what changed that caused you to leave?

Padrón: Around 1952 our family was buying tobacco in the entire area of Pinar del Río. We had a contract with the H. Upmann factory for picking, curing, sorting and deveining the tobacco. They made Montecristos, among other brands.

CA: What happened after that?

Padrón: After the revolution and Fidel, there was a problem with the tobacco industry: they took it. In 1959, during the revolution, our farm totaled about 250 acres. That land got nationalized. One part was taken to raise geese.

CA: How did it happen; did someone knock on the door? The soldiers came, the police came, the mayor came? Who?

Padrón: I really don't know because by then I was already gone; but they took it. They left us with about five acres.

CA: When did you come to America?

Padrón: I left in 1961, but I was no longer in the Pinar del Río after the revolution because I was in Havana trying to leave Cuba.

CA: Did you have a problem getting out of Cuba?

Padrón: Yes, I actually had a lot of trouble but I was able to get out and go to Spain.

CA: What happened after that?

Padrón: I went from Cuba to Spain and then came to America, first to New York, where I ironed clothes for two months in a dry cleaner.

CA: And then you went to Miami. Why Miami?

Padrón: I hated the cold weather. [laughter]

CA: How did you get into the cigar business in Miami? When did the Padrón cigar actually begin?

Padrón: I started it in 1964 when I came to the U.S. I got the idea that I could make a cigar; although it would not be exactly like the Cuban cigar, it would be similar. I wanted to provide the smokers in Miami with cigars similar to what they were used to smoking. I began with 200 cigars a day with one roller.

CA: Is that the same place where you are now?

Padrón: No. I just had one roller.

CA: Isn't your Miami factory in Little Havana, near Ernesto Carillo's El Credito?

Padrón: Ernesto is on 8th Street and 11th and we are on Flagler, which is eight blocks north and four blocks west. But at first, I rented a space that cost me $62 per month; I rented it on March 29, 1964. I applied for the license to be able to manufacture cigars but I didn't have the money for the bond. I just didn't have the money--I had nothing.

CA: Were there many cigarmakers in Miami in those days?

Padrón: Just one--Camacho, I think. There may have already been one other brand, Primo del Rey, being made there.

CA: How did you decide what tobacco to use? Your experience was with Cuban tobacco, and of course it was unavailable.

Padrón: I tried blends with tobacco from Puerto Rico, Brazilian mata fina and Connecticut broadleaf. I ended up making a blend from those tobaccos and I also used some Cuban-seed tobacco from Honduras later on. I never made a green cigar with the double claro wrapper. I just started out with 200 cigars a day. Then it occurred to me to invent La Fuma.

CA: What was the tobacco you used in that cigar?

Padrón: It was all Connecticut broadleaf.

CA: One hundred percent broadleaf?

Padrón: One hundred percent, and you won't believe the price. The grower sold me 100 pounds at $70. That's 70 cents a pound.

CA: Did you have a shop where somebody could just walk in and buy cigars?

Padrón: I sold my first cigar six months after I rented the space because of the problems with my license. I began with what was called El Cazador. It had a rounded head with short-fill tobacco. At that time, one of my first clients wanted a big black cigar with the curly head like the ones you would be able to get in Cuba. So we called it a fuma. Normally, it's what a roller would take home with them at night. The cigars we made during the day, I would go out to sell at night.

CA: What was the retail price of the cigar?

Padrón: Thirty cents. [laughter]

CA: If you were a grower, how did you know how to roll cigars?

Padrón: The important thing about cigars isn't in the rolling of it, but in the processing of it and in the curing of the tobacco. Throughout the history of the cigar industry, rollers have never been able to establish and maintain factories. Even the best rollers, the stars if you will, have failed when they tried to start factories. The important thing is to know how to make a good blend and cure the tobacco well.

CA: When and why did you shift from Connecticut broadleaf to the other tobacco that you started using?

Padrón: I could no longer find what I needed to supply the Cuban market in Miami. It's not that there wasn't enough broadleaf, seeing how no one really consumed broadleaf in the United States. But I really did put it through a lengthy process of curing it, and inventory was pretty tight. In 1967 a gentleman came looking for me, sent to Miami from Nicaragua by his boss to show me some samples, so that I could see the tobacco that they were growing. They wanted my opinion. They told me that someone had told them that their tobacco was no good. They were on their way to Europe to try to sell it. I told them that in Europe they weren't going to be able to sell this. I told them that when they returned they should come and see me, and I would go to Nicaragua to inspect the tobacco and the fields. I noticed immediately that the quality of the tobacco was very good. That's why I agreed to go there to see the farms. They took me to a place called Jalapa, in Nicaragua. That was before any foreigners were there in the tobacco industry. They had harvested some tobacco but not much, and they didn't have buyers for that. They didn't know what they were doing.

CA: You obviously liked what you saw.

Padrón: Oh, absolutely.

CA: When did you start making Padrón cigars with Nicaraguan tobacco?

Padrón: 1967, in Miami. I was already making 7,000 cigars a day at that time.

CA: How much is that in a year?

Padrón: More or less two to three million. But even that wasn't enough to supply to the Cubans. So, I went to Nicaragua [in 1970] to try it out there with four rollers.

CA: But it hasn't always been easy in Nicaragua. What's happened to you there? Where was your factory?

Padrón: The factory was located at the center of Estelí, about 100 miles north of Managua. In 1978, Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, the editor of the newspaper La Prensa, was killed. The day was January 10, 1978. At the time, there were about 20 Cuban exiles involved in the tobacco business there.

CA: How many factories existed?

Padrón: At first, just three. The one owned by the president, Anastasio Somoza, Fonticiella and mine. After that, there were some smaller ones, but they didn't have any strength; they were small. I never liked to get involved with the country's politics. You can't really make allies. I had a friendship with Somoza; I helped him and they were grateful for the help I gave regarding tobacco. In truth, all the Cubans in the tobacco business had dealings with Somoza. I told them I would help out but that I wanted to continue being independent. In April 1978 the riots in the streets began. On May 24th the mobs burned more than 20 houses, including my factory, Fonticiella and another small factory that was there.

I was in Costa Rica at the time because I figured it was a good idea to check out the situation there, considering all that was going on in Nicaragua. The mob burned the factory and some small quantities of raw tobacco, but not all of it. The people of Estelí were upset that the factory had been burned, and within a month we were operating at full capacity again. But I still continued looking for a new location, just in case, and that's when I began preparations to open a factory in Honduras.

CA: Was that in the summer of '79?

Padrón: Yes. I had the tobacco, because to me the most important thing in a factory is to have the prime material ready. A manufacturer can be without money but he has to have his prime material ready if he wants to maintain his blend. I had close to 350 bales of tobacco. On July 16, before the [Nicaraguan president's] palace fell, we chartered a plane. We loaded those bales that I had and flew them to El Salvador, and from El Salvador to San Pedro Zula to Puerto Cortez and then on to Tampa. I still have a few bales there with the numbers.

CA: It was your tobacco?

Padrón: Yes. I knew I had to save my prime raw material. I had chartered the plane because I needed to save it. We took it to Tampa first; from Tampa it went to Honduras. We even ended up using some of it again in Nicaragua.

CA: What happened after the Sandinistas won?

Padrón: When the Sandinistas had won, my laborers put on a demonstration in the village: "Bring back Padrón!" In the main park, you know the people that are always there. My workers called me from there, "What do we do? Do we continue with the factory? You have tobacco here." In fact, there were 700 bales.

CA: But there had been a lot of fighting in that part of the country, and Estelí was bombed more than once.

Padrón: Yes, but the workers had protected the factory, because I had told them to guard it or I would never return. The factorytook three hits, knocking down a wall. But the only thing I lost during the war was a $70 tobacco scale.

CA: Incredible--even during September of '78 when the city was taken over by the Sandinista rebel army for three weeks?

Padrón: Yes. We only lost that amount. So what to do? I told [my employees] to start manufacturing again. I had confidence in them, and they did it. Now I didn't go there right away. After about a year I went back because they needed more tobacco. There were about 300 people in the factory. The local commandant was there and I spoke to him, saying that he knew me and he knew I had worked with everyone, including Somoza and the Sandinistas.I asked him if they thought I was the right person to continue operations at the factory. I said to him that "if you tell me that I am in the way here, then you are saying it to me for the first time. Do you see all those people there? They have all made their living from this factory for 10 years now. I think you have the final word, and I would like for you to tell me what it is that you think." Just like that. In front of all of them, the Sandinista official told me, "We know who you are and we also know what you are. You can remain here. We are going to give you a guarantee that you will not have problems again."

CA: This was in 1980?

Padrón: Yes.

CA: What was happening in the fields at this time? Were you planting and harvesting?

Padrón: No. Before the revolution we were able to plant at traditional times in October and November. After the revolution, the blue mold disease became a serious problem and we had to push the plantings back. But our problems were greater than that. First the contra war started and there was fightingaround the frontier and throughout the tobacco-growing regions. Then, on April 30, 1985, the blockade was ordered by Reagan. I suddenly had another problem. I had tobacco in the warehouses and I was in a situation where I wouldn't be able to bring it or the cigars to the United States. The U.S. government gave us seven days to get out our contracted shipments to the United States. We chartered two planes to bring the tobacco back to Tampa. But we couldn't get it all out, because the planes had to be back in Tampa by May 5, or they would have seized the planes coming in. We did get an exemption from the Treasury Department that gave us until October to get the rest of the tobacco out. In those six months we worked until 9 every night, getting the tobacco out of Nicaragua by rolling it into cigars. We made 6 to 7 million cigars in that time, but when our extension ran out there was still tobacco there. So they kept making cigars, about 600,000 of them, which were left there until the blockade was lifted in 1990.

CA: How many cigars were you producing in Honduras during those five years?

Padrón: It depended. There were days that we were producing 10 to 12 thousand cigars a day. Today, we are producing about 5,000 a day in Honduras and 12,000 in Nicaragua.

CA: After everything, why did you return to Estelí in 1990?

Padrón: I had a factory, a house and six warehouses. In Honduras, I didn't really have anything.

CA: What's happening in Estelí now?

Padrón: At one point, there were about 19 factories and now there may be 10 left. Of those 10, not all of them are working every day.

CA: Do you think that some of those factories have ruined the industry here by producing inferior cigars?

Padrón: I have said this many times. That is one of the things that in Cuba had to be controlled in the early 1940s, when there was a boom in cigars in Cuba. When the boom stopped, how many factories were left standing in Cuba? Only the ones that were true cigar factories, the ones that had brands behind them and control over the quality. That is the same thing that is happening now. Many people have gotten into the cigar business without knowing anything about it. As a result it discredits the good cigars on the market. There has been no control of quality.

CA: Of those 10 factories, how many will remain?

Padrón: I think about four will survive. Maybe some of the smaller ones will survive, but we won't know that for a while.

CA: Do you own land in Nicaragua?

Padrón: I own two farms. One is occupied right now by some vandals; they destroyed the barn about seven years ago. We haven't been able to get that farm back. Hopefully we are going to get it back in the next few months.

CA: But you own it?

Padrón: Yes. And we also own another one that we are producing tobacco on.

CA: How many cigars did Padrón make in 1997?

Padrón: About three and a half million or so.

CA: It's not that big an increase from the old days. But the average price must be higher?

George Padrón: Yes, and the style of the cigars have changed, too. Back then, a lot of the production was short fill.

CA: What is the history of the Anniversary, one of your best cigars?

George Padrón: I'll answer that. Before we entered the nationwide market in 1993, we had primarily produced for the Miami area. At the time, we had sold more than 130 million cigars, mostly in the Miami area, thanks to a number of things, including write-ups in national newspapers. We also had done some direct mail sales.

CA: From the Miami factory?

George Padrón: From the factory. We also began to have production in Honduras in 1979 as well as Nicaragua.

CA: Where were the cigars rolled?

George Padrón: They have been rolled in Nicaragua and Honduras. We stopped producing out of Miami around 1974 and all production shifted to Nicaragua at that point.

CA: Last year, you produced 3.4 million cigars. How many were made in Honduras and how many in Nicaragua?

George Padrón: About 30 percent of the cigars come from Honduras.

CA: Do you still have back orders?

Padrón: No, we stopped taking back orders two years ago. If you run out, order from me. You can't have so many orders just sitting in the computers. For example, we got a shipment into Miami of 300,000 cigars a week ago. By the end of the week, we got rid of all of them.

CA: How many cigars do you expect to produce in 1998?

Padrón: Four million, if possible. I can't predict really how many will be made and anyone that does make those predictions doesn't know what he is doing. It has to do with the processing and the curing of the tobacco. For example, that little cigar [Principe], do you know why are we producing that little cigar? This way we can use a smaller wrapper leaf that comes from a lower part of the plant. Last year, we didn't produce that size, and we made fewer cigars.

CA: What is the production of the 1964 Anniversary?

Padrón: The Anniversary production last year was about 150,000 cigars. This year it may be that we will approach the 300,000 mark; we have enough wrapper in inventory to do that.

CA: It isn't much.

Padrón: No it isn't, but for me this cigar is the apple of my eye. I want the integrity of this cigar to remain constant. If I would have wanted to produce 2 million of these cigars I would have, but it wouldn't be the same cigar.

CA: How would you describe the strength and the flavor of the Anniversary?

Padrón: The flavor is my secret [laughter]--a secret I won't be sharing with anyone. It is a medium strength. People say that it is a good flavor. I smoke my own cigars and I think it is good but I will let the public dictate.

CA: Is there any special taste that you find in your cigar which makes it...

Padrón: I produce tobacco to my taste but I can't smoke it all myself. First of all, the filler, which is the detail that others have overlooked these last few years, needs to be well cured. But the wrapper, too, must be well aged so that when you smoke a cigar, your mouth is left with a smooth taste.

CA: What was the reason you created a 30th-anniversary cigar?

George Padrón: We introduced the Anniversary in 1994 to commemorate our 30th anniversary of being in business. It was something special as we went to nationwide distribution.

CA: Are you going to continue that line for many years to come?

Padrón: It will continue.

CA: Why did you decide to box-press the cigars?

Padrón: Because they reminded me of the squared cigars of Cuba that I used to smoke. It is the only thing that I have actually copied from a good Cuban cigar. Everything else about the cigars is based on my own experience. Once, in 1965, I was making a No. 4 size and selling it for 30 cents apiece. I was selling the box for six dollars. Someone came to the factory and told me that he had 1,000 empty boxes of H. Upmann. He said he'd pay me $10 a box if I'd just make a cigar just like the H. Upmann. I told him that the one I would make for him, if I would even do it, would be better than the H. Upmann. I said I had no need to imitate anyone else and I wasn't going to start with him. After that, I could still go to sleep at night with a clear conscience.

CA: So many other factories have contracts to make other brands. Why don't you do that?

Padrón: When you have a factory, you must make the cigars all the same. A cigar factory that has to make more than one brand can no longer control its production. You can't make one brand and distinguish it from another; it's impossible. In my case, I never wanted to do it. If I had wanted to, this year I could have produced 10 million cigars or 20 million, having someone make 5 million here and 7 million there. I tell you: no no no. Why? Because we are concentrating on having the best brand, including those produced in Cuba.

CA: George, when did you enter the cigar business?

George Padrón: I've been in the business my whole life.

CA: In Miami?

George Padrón: I was raised in Miami along with the rest of my family.

CA: Where did you do to college?

George Padrón: I went to Florida State and the University of Miami. I graduated from Florida State in 1990 with my bachelor's and then my master's from University of Miami in 1992.

CA: Go Hurricanes. Going back to Cuba--when you were growing and processing tobacco, did you ever sell cigar tobacco to factories in the United States?

Padrón: No. I only sold to the brokers. All the business in Cuba was done through the brokers and they sold it to people outside the country.

CA: How did you feel when you were in the tobacco business in Cuba in the 1950s when Cuba had factories to make finished cigars, but they were shipping bulk tobacco to the United States where "Clear Havana" cigars were made, almost in competition with the Cuban products?

Padrón: At the time, you had to sell the tobacco. For the growers, it worked in our favor. We needed to sell the tobacco. I want to make clear that when we shipped the tobacco to Tampa, the blend was already planned out, the recipe for the cigars, if you will, was already decided upon. All they had to do was follow our plan.

CA: Tomorrow morning when you wake up, you read The New York Times, and it says the embargo has ended. What is your dream?

Padrón: I'd get to the Pinar del Río as quickly as possible and find the men that are over the age of 50 that I once knew, that are probably not today working in tobacco. I'd have a factory in Pinar del Río. I'd first help the growers with fertilizer. But that's not going tohappen with Fidel in power.

CA: Would you start a factory for processing tobacco or cigar making?

Padrón: Cigar making. But I'd also get some farms I know.

CA: Didn't you get in trouble once in Miami because you went to Cuba?

Padrón: Yes. This is an important story. I was a revolutionary. I was very involved in the Cuban revolution. But when I left Cuba because I didn't like the way the revolution was going, I had left behind a few friends that told me not to forget about them, that they were going to see just how far they could go in Cuba. But many of them ended up in prison.

CA: The majority of them were revolutionaries, correct?

Padrón: Exactly; the majority were, well, actually all of them were. We went with a group of six people from the United States to see if we could get them out of prison.

CA: What year was that?

Padrón: 1978. I had never thought I would return to Cuba until the conditions that had made me leave had changed. We arrived in Cuba October 20, 1978, in the evening with the intention of getting my friends and as many other political prisoners released. At that point, we were not able to get them released, but we did interview one. Later during our visit, on a Saturday morning, they took me to see the University of Havana. At around 1 p.m., we went to a government house and Fidel Castro appeared.

We started talking. We were trying to figure out a way to have the prisoners released in an orderly fashion. We were calculatingit all: how many prisoners there were, how they could be taken out, the planes. We needed to have some organization to be able to get those prisoners out of the country. We were sitting at a table and they brought out a box of Cohibas. They gave me that box as a gift so that I would be able to try the cigar. We still hadn't discussed the prisoners, since this was at the beginning of the visit. I had a box of my cigars on the table and I was sitting at the head of the table. Fidel said to me, "Padrón, they tell me that you are making cigars in Miami. Can I try one?"

CA: You had met Fidel before?

Padrón: Yes, of course. I put the three cigars on the table; I wasn't about to just put one down, I put the three there for him to choose. He takes one and I take another, so now I have one left in my pocket. This is the way it all happened. I began to smoke the cigar as did he.

CA: Had he removed the ring?

Padrón: He had taken off the ring. So we started to talk of Nicaragua because I had told him that we harvested three times a year in Nicaragua. He asked me how that was possible. At that point, we still hadn't touched on the issue of the prisoners. But when the conversation turned to that subject, there were no reporters or anyone else, just our delegation and his people. But then after the discussion, the reporters entered, including someone from The New York Times, and [Fidel] tells me, "Hey Padrón, this cigar is very good, but I think that you have copied the ring. Let me see one." So I handed one over to him. That's when the picture was taken. But that same afternoon we returned to Miami with 42 prisoners.

CA: You were able to get them freed?

Padrón: Yes. When we got to Miami, it still wasn't a big thing until the picture hit the papers. It was something else after that. Padrón Communist was the headline, and yet they didn't know the sacrifice we went through to get people out of prison.

In November 1978 there was another dialogue, about them releasing to us 300 prisoners. Although there were not any big problems, the people were saying that we were communists because we were going over to where Fidel was. And they kept bringing up the cigar thing. Anyway, they released to us 300 prisoners. But I still hadn't gotten the three I most wanted to get out. The Cubans gave me a chance to go into the prisons and look for these guys. Finally, it was after that trip that the bombs started.

The first bomb was on March 24, 1979, but it didn't explode. Extremist groups put it on the side of our Miami factory and a nephew of mine found it and called the bomb squad. After that, the anti-Castro folks bombed us three more times from 1979 to 1982. I must have done something in my favor, because during the bombings, I broke my own sales records in Miami. I put a large banner outside the factory, a saying by José Martí that read: Men are divided into two camps/Those that Love and Build and those that Hate and Destroy.

You know, I took nothing from Fidel. The Cuban government respected me and respects me still today because I made myself be respected. I never said that the situation was good in Cuba, because the system does not work. I never said it to the government nor am I saying it now. I think that they have been wrong; they have to change. They can never say to me that I joined them. All that happened was they treated me with respect and I treated them with respect.

CA: At last count how many political prisoners were freed by the process that the group initiated?

Padrón: 3,600 prisoners.

CA: That's incredible.

Padrón: It was followed by some sacrifice. Not a business sacrifice, because I have already told you that the business did not decrease. On the contrary, it increased. It was what happened with my family and the tension in my factory. I had to put a camera system up to protect ourselves. It's still there. My car had to have an automatic starter. My house had alarms. That is the sacrifice. In regard to the business, I think that the people in Miami realized that what was happening was an injustice. Because the result of what we did came out later.

CA: Do you have any pictures of you or your family when you lived in Cuba?

Padrón: All that was left behind, but if I were to bring a picture of the farm now, it would cause me great pain for you to see it because it is destroyed.

CA: How do you compare the taste and flavor of your cigar to a Cuban cigar?

Padrón: The Cuban cigar is still different. We have tried to re-create the flavor from the early days, but it still isn't the same. We have come close to it but not quite. I would like to say that all of Cuba isn't good for tobacco growing. There are some parts that are just perfect for growing but then there are areas that are useless, just like in Nicaragua. For example, in Nicaragua there are recently opened-up areas that are not good. We have farms in certain areas, and I have tried tobacco from every farm in Nicaragua--all of them. I have arrived at the conclusion that there are just some farms that can't be blended together. It has taken me five years to get the right tobacco in the ground and it still hasn't become the cigar that I'm capable of producing in Nicaragua. The goal has always been to provide a substitute cigar for the Cubans living in Miami. But which is the better cigar? It's not that one is better than the other--they are different. Now there is no doubt that a Cuban cigar smoker can have one of our cigars and he will be satisfied; that is an important word because there are many cigars that don't satisfy. You smoke one of our cigars, and you notice that it has flavor.

CA: Is all the tobacco used for the regular Padrón cigar grown in Nicaragua?

Padrón: Yes, all of it, and all of it is Havana seed. That's one of the problems that we are having. When you see a picture, you'll notice how different one plant of Habano is to just any ordinary plant: you'll notice the veins. Never does one vein coincide with another in the Habano tobacco.

CA: Before the revolution of the Sandinistas, they say that the tobacco from Nicaragua was the best outside of Cuba. But during the revolution and the Sandanista government, the quality of the tobacco and the cigars suffered. Are we getting to where the tobacco is returning to its original state?

Padrón: That's a tough one. You must control quality, from in the fields to the point that the cigar reaches the mouth of the smoker. But there can be problems all along the way. For instance, our warehouses are absolutely full this year with over 3,000 quintales [bales weighing about 200 pounds each] of tobacco, and we don't have anywhere to put more; if we tried it wouldn't be kept in proper conditions. Or as another example, in Nicaragua you can't use a seed from Indonesia or Cameroon, but the tobacco from a Connecticut seed went very well there for a while. I don't know what has happened now, because it's been very hard to get any Connecticut-seed wrapper out of Nicaragua since the war.

So, we've had problems with the seeds, with fertilizer, and that doesn't even mention the blue mold outbreaks that we've been having since 1978. For my own part, I did a little better with the seed varieties this year. I believe this year's crop is going to give my tobacco the flavor it had before the revolution. With the combination of the climate, seed and the fertilization in Nicaragua, I think that it could be a lot like Cuba. Cuban tobacco has an easier curing process than in Nicaragua. The curing of the Havana-seed tobacco, for example, in Pinar del Río or Partido, is simpler to do than in any other country, and as I always say, "The most important part of any cigar is in the curing process." It needs to have its time. When you smoke a cigar that is raw, you'll notice it because you'll see that it is sour or it will just bother your mouth, and that is what I have taken the most care of in my production.

CA: They say you are a hands-on cigar and tobacco man.

Padrón: I am involved in everything, every aspect, all things. For instance, a bundle of tobacco arrives and the first thing I do is unwrap a leaf to see how it is going to burn, to test if it is ready, raw or not. That is something that I won't ever stop doing. There are so many stages in the process. For example, how long are you going to give a leaf before you pick it? If you pick it too soon it's no good and if you pick it too late it's the same problem. If you knew how many times one person had to touch a well-cured leaf--it is like 200 to 300 times. From the planters to the pickers, the ones that take the young leaves off the plant. It seems almost endless.

CA: Your family has been involved with the tobacco business for a long time. We can say that for the past seven or eight years things have been much better. Are you satisfied with the level that the family has reached?

Padrón: I think, yes. In [my family's] minds they have to be thinking that this is a tradition. They have to follow it with a seriousness in the same way that it was shown to me. There is an anecdote: When my grandfather was in Cuba, the deals were made without contracts. My grandfather had a deal for tens of thousands of pounds of tobacco. He would tell the buyer the price and then another buyer would come along offering him 10 pesos more, which was the same as the U.S. dollars. He would tell the second buyer that he had already given his word. He would call his sons and tell them the story about how he had turned him down and one of his sons said to him, "But Dad, you are losing 30,000 pesos with that deal." He would tell him that his word and his name were worth more than 30,000 pesos. I want my family to keep thinking in the same way: In this business you have to be serious. Because the one that is not serious won't make it.

The most important thing in making cigars is that when you go to take a cigar, you have the confidence that each is the same. I have the pride in saying that I have spent 30 years giving people a good cigar. I have a cross to bear: I have many older men that I have to sacrifice myself for because they are the ones that helped me when I was starting out. You have to remember who was the one that gave you a hand when you were in the most need, because when you are on top everyone is there. That is what I am leaving behind, thank God, what I am teaching them, hopefully. They all work. No one has gotten involved in drugs. I can say that my wife, my daughter, my other son and my nephew work, and if there were any more they would be working, too. That they meet their responsibilities, not to fall in the trap of not doing what they are supposed to. You have to have a seriousness in this business. We could have gone public so many times, but no, it has to remain in the family. That name has to be protected.

CA: And George, how do you feel?

George Padrón: I feel very satisfied when we started selling to the stores, when we went to the national market. Although we had an established brand, it still wasn't established in the eyes of the American consumers. I give thanks to God every day that I have had the opportunity to see all the stages that this company has gone through in the last 10 years.

Padrón: A brand and factory of cigars is like a child. It is born, it crawls, it takes small steps, it walks and finally it runs. Whoever tries to take one step without having completed the ones before it breaks his nose. That is why you have to take your time. When I started my factory, I sold the 200 cigars we made each day at night. All I wanted to do was make a good cigar, and I've done that. We have no middle man. That is also very important. It has helped us get through some tough times, like when we were targets here in Miami.

CA: What about the future?

Padrón: The patrons of Padrón cigars can be assured that we will not be letting them down, just like they haven't let us down, smoking Padrón cigars for over 30 years. We have had customers for that long; we can name them--Cubans as well as Americans. Those people have been loyal to us because we have been loyal to them. *