A Conversation with Facundo Bacardi

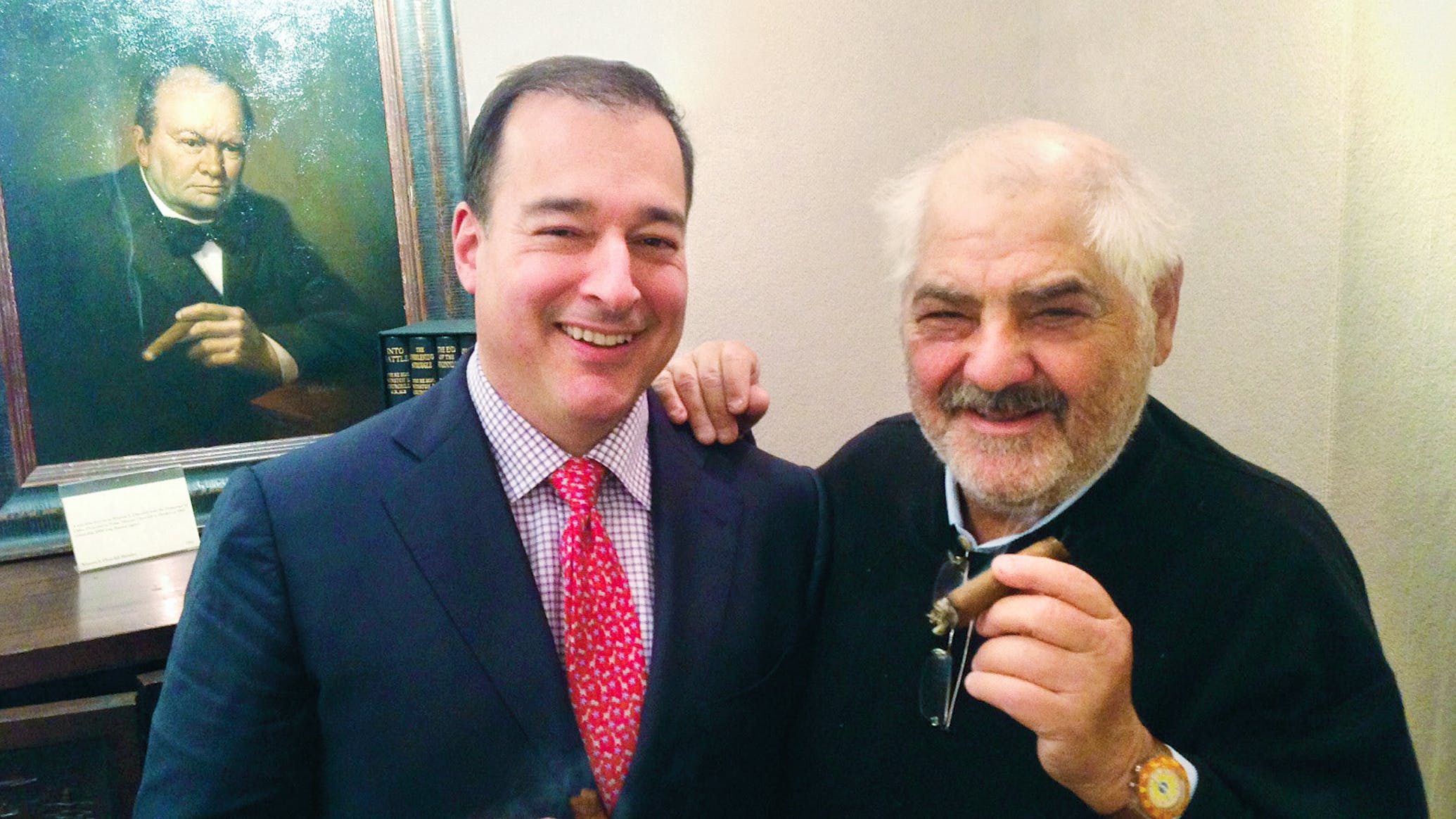

Facundo L. Bacardi, the great-great-grandson of Bacardi Ltd.founder, Don Facundo Bacardi Masso, has served as chairman of the board of Bacardi Ltd. since 2005. In his wide-ranging interview with Marvin R. Shanken, the chairman of M. Shanken Communications, and the editor and publisher of Cigar Aficionado, Bacardi talked about his company’s role in the global spirits business; the company’s major brands include Grey Goose, Dewar’s, Bombay Sapphire and Bacardi rums. Most of the interview was for publication in Impact, a wine and spirits newsletter, and focused heavily on the company’s $5 billion business.

But of special interest to Cigar Aficionado, Bacardi also spoke at length about the family’s Cuban heritage, and provided a window on his thinking about the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba, which has been in place for more than 50 years. The Bacardi family fled Cuba in the wake of Fidel Castro’s revolution in 1959, after its distilleries and assets were seized by the new government. Bacardi talked about the hopes the family has to return to Cuba some day, and what that might mean for the company in the future.

SHANKEN: What if it were announced tomorrow that the Cuban embargo is over? Your flagship Bacardi brand was founded and built in Cuba. What’s the Bacardi family mindset on taking advantage of a changing market, where you’d have the freedom to produce and market rum and other products of Cuban origin in Cuba?

BACARDI: I can’t tell you what will happen tomorrow. But I can tell you that the vision of the family and the company is to come full circle. We will be back in Cuba, and we will invest beyond what it will take just to build the brand. We see Cuba as our home. I would say about half our family members were born in Cuba. We left before the revolution, and we have every intention of going back, rebuilding our business and helping the Cuban people.

SHANKEN: Have you been to Cuba?

BACARDI: I have never been to Cuba.

SHANKEN: I have been to Cuba a number of times. I got goose bumps when I visited, because I know the history of the Bacardi family there, and having met a number of Bacardi employees and family members. I think it could be very, very exciting, not just for the family, but for the company and the brands—particularly the Bacardi rum brand—to be able to go back to its roots and offer the world a Cuban rum.

BACARDI: Absolutely. Offering the world a Cuban-sourced Bacardi rum—it will happen. When we look at Cuba, to us it’s really not a commercial endeavor. We’re going to do all the commercial things because that’s where we’re from. You never forget where you come from, and for us, we absolutely will be back there. But for us as a family company, for family members and for our shareholders, it’s less about the commercial endeavor and more about reconnecting with our birthplace, with our homeland.

Bacardi’s history is so closely intertwined with that of Cuba. Raul Castro’s father-in-law worked at Bacardi for many years. His father-in-law also was one of my grandfather’s close friends. Fidel Castro went to school with my cousins. Cuba is a small country, and there was this diaspora of Cubans that left, including my family. We broke off and went to about 15 different countries around the world. A lot of companies will look at Cuba as a commercial opportunity, but we don’t necessarily look at it that way. We see it from the perspective of Cuban exiles returning home. And what do you want to do when you go back home? You want to give, you want to help your fellow Cubans rebuild society and provide opportunities to them. So the commercial part is a function of what we want to do as a family.

SHANKEN: I understand. It’s a social responsibility to your home. I see that the Cuban people are honest and hard-working. Never once has a Cuban person ever said anything negative about the U.S., even though we created the embargo over 50 years ago. Do you have any sense, other than hope, as to when the embargo will come to an end?

BACARDI: For Cubans who left in 1959 and 1960, [the return] was always next month. That was always the hope—that something would change next month. Even my father, at the age of 14, joined a militia when he left because the hope was that they would go back. Eventually, they realized they weren’t going back any time soon. The months turned into years, and the years turned into decades. Those Cuban exiles, particularly those that came to the U.S., became part of the U.S. and became Americans in many ways. They became Americans, yet they never lost their connection with their home country.

SHANKEN: At Cigar Aficionado, we have editorialized a number of times over the years that it’s time to end the embargo. We’re on the record. Why doesn’t the Bacardi family undertake a public campaign to draw public attention to this injustice and get this embargo over, so the people in Cuba can regain the freedom they had and the hope for prosperity in the future? Most of today’s citizens in Cuba are victims of their government. Why doesn’t Bacardi adopt a public position of getting Washington to look at the facts and understand this would be great for both countries, to expand commerce, to expand jobs and to help our neighbor? The Castros are in the past. Changes are occurring in Cuba. Everybody says that on the day that Fidel Castro passes away, America will act. But why are you waiting—why are you not proactive? You’re a big corporation.

BACARDI: We have a big family, and as in every big family, we have differences of opinion. Some family members are pro-embargo, and others are anti-embargo. One thing is that we’re not politicians. The people who really care about Cuba, not from a commercial perspective, but from a true desire to help Cubans, whether you’re pro-embargo or anti-embargo, those on both sides of the issue are already doing that.

SHANKEN: Why would a Bacardi family member be in favor of the embargo? What would be the motive?

BACARDI: It’s because there really are no basic freedoms in Cuba. There are no rights. It’s a dictatorship. I can speak for my family in saying that the overriding goal when it comes to Cuba is to have an open and free society. So when you don’t have an open and free society, and people believe that the embargo is applying pressure to help force movement to an open and free society, people support an embargo. So what do you have? You have Cuba, which went from a very hard-line stance under Fidel, to Raul, who is taking baby steps. The society is slowly opening up a bit, and there are reforms. So long as reforms continue, the people who benefit the most are the Cuban people. Every country does things at its own pace, and Cuba is no different. It’s doing things at its own pace. I can understand that the Cuban government doesn’t want to run the risk of a revolution, so they’re implementing these changes in piecemeal fashion over a period of time. The question is, will Raul go all the way, or not?

SHANKEN: There are a number of people who feel that ending the embargo would only accelerate the creation of an open society, because people could then own property, get jobs and export products. Cuban society would prosper, and that would be good for the Cuban people. The dictatorship portion is the past, not the future.

BACARDI: The benefit that Cubans will have will be opportunity from companies coming into Cuba and wanting to build businesses, thus providing jobs. As for real estate, I think many Americans don’t realize, that most real estate in Cuba is encumbered by claims from before the revolution. Those claims have to be worked out before anybody goes in there and starts buying land. In Eastern Europe, for example, there has been a process to deal with such claims. The idea that you could go down and buy land in Cuba is, frankly, unrealistic.

SHANKEN: I was just thinking of people owning homes.

BACARDI: You’re beginning to see that, little by little. This is one of the reforms that Raul Castro has implemented—allowing people to buy. We live in a world in which we as Americans have a view as to how our society should be. In many respects, we want other societies to be run the same way, because we believe that we’re doing the right thing. But in other societies, they don’t necessarily believe the American way of doing things fits their culture.

SHANKEN: How old are you?

BACARDI: 47.

SHANKEN: Your great-great-grandfather was the founder. That connotes a certain uniqueness.

BACARDI: No, that’s not true. To be clear, I’m the third-youngest family member of the fifth generation. We have people who are in the eighth generation. So my great-great-grandfather is a great-great-grandfather to everybody in the fifth generation. I have a brother, a sister and many cousins who share the same great-great-grandfather.

SHANKEN: But you are the chairman. How did that happen?

BACARDI: I’m the chairman only because I have the support of my family. When you’re a family member and the CEO—in charge of the day-to-day operations of a company like ours—you function in a very different way from that of a non-family chief executive. Your vision reflects a unified approach by the broader family. Recall that until 1992, Bacardi was comprised of five independently operating companies. In that year, we reorganized under a Bermuda-based holding company structure.

But a reorganization doesn’t mean those different cultures are assimilated overnight. The family members at the helm were always very good—making everyone understand they were working for the Bacardi family. As our senior family members retired, we started elevating non-family members who had worked at Bacardi for a considerable time. That was the beginning of a long transition away from simply being a family-run company. In 2005, we moved to split the CEO and chairman titles. I became chairman, with a non-family member who worked at a major consumer products company as the CEO.

SHANKEN: Bringing in new blood, people with new vision.

BACARDI: Bringing in people with new insights from different industries, who’ve contributed immensely. But while they were all wonderful, they came from companies that were 10 times bigger than ours, with completely different operating methods. So we ended up with a different approach to managing a family business. In many respects, Bacardi hasn’t changed in 152 years, in that it’s still 100 percent owned by family members. Those family members view the company as something that my great-great grandfather and his descendants have devoted their lives to building. They don’t see Bacardi as a company where they simply own shares and follow stock quotes. It’s something beyond that, and something far bigger than any one family member. It’s a legacy.

SHANKEN: They’re like passengers on a ship that will continue many years into history.

BACARDI: Yes. We see ourselves not as shareholders or directors, but as stewards of a legacy handed down to us—and a legacy that we will hand down to our children and grandchildren. It’s something to which we’ll devote everything we have. The return that resonates most is the idea of handing off Bacardi in a far better position than when we received it. If we’re able to do that, we’ve done our part as stewards. So it’s a different mindset. In today’s business environment, it’s all about making the next quarterly or annual numbers. Not with us. We are making investments for the long-term. Sometimes we make investment decisions where we won’t see a return for five, 10 or 15 years down the road. That’s the right thing to do for a privately held family company.

SHANKEN: Which a lot of public companies can’t do.

BACARDI: They can’t. We take a completely different approach. When someone comes into Bacardi from outside the industry with no family company experience—from big, bureaucratic companies where it’s easy to throw money and people at a problem—that’s exactly the opposite of who we are.

BACARDI: Don Facundo Bacardi Masso had four children, and hence they represent the four branches of the family.

SHANKEN: How many Bacardi family members are there who are shareholders?

BACARDI: We have about 900 family members, including spouses.

SHANKEN: How many people are on the board?

BACARDI: There are 16 people on the board of which 15 are independent directors.

SHANKEN: And how many of the 16 are Bacardi family members?

BACARDI: Seven.

SHANKEN: Which is not a majority. Shouldn’t the Bacardi family have a majority? A 152-year-old family business, and the board is not controlled by the family?

BACARDI: While we have seven family members on the board, we also have three representatives of family members.

SHANKEN: That would be 10.

BACARDI: Yes. The representatives are not family members, but every one of them exercises their judgment in terms of what’s in the best interest of the company, knowing they are there representing the family’s long-term interest.

SHANKEN: What about the other six?

BACARDI: One of the six is for the CEO and the other five are professionals not affiliated with the Bacardi family.

SHANKEN: Could you tell me a little about some of the independent directors who serve on your board and their backgrounds?

BACARDI: Sure. Robert Corti is the retired CFO of Avon Products and the current chairman of the Avon Foundation. Georgia Garinois-Melenikiotou is senior vice president of corporate marketing for the Estée Lauder Companies. Patrice Louvet is group president of global grooming at Procter & Gamble. John Galantic is president and chief operating officer of Chanel. And Mike Dolan is the CEO of IMG and former executive vice president and CFO of Viacom.

SHANKEN: The board members who aren’t family members—do they turn over every two or three years, or do they stay on the board for a long time?

BACARDI: They typically remain on the board a while.

SHANKEN: Have you or your family ever considered selling out?

BACARDI: Never.

SHANKEN: It must come up at board meetings.

BACARDI: Never.

SHANKEN: Not once?

BACARDI: Not once.

SHANKEN: How about when talking at the bar, after the meeting?

BACARDI: Never. It goes back to what I was saying about being a steward of the company. We don’t sit around and say that our opportunities have been exhausted. We see tremendous opportunity ahead.

SHANKEN: What’s your vision for the next 20 years of Bacardi?

BACARDI: My vision is to see Bacardi grow organically and grow through acquisitions. We will never be—and don’t want to be—the largest company by case volume. The vision is to be the premiere premium spirits company where consumers see that our products are made by a family company that cares about its history, its employees and its customers. Profitability is important to us, but there’s something far more important. We’re a family company, not a public company where it’s all about profit. We see ourselves as part of a global community in which we want consumers to respect us for what we stand for, and not see us as just another company.

Editor’s Note: In 1994, Marvin R. Shanken interviewed Cuban president Fidel Castro. For readers interested in a historic document filled with insights into Cuba and the Cuban Revolution, read the interview here.