The Sherry Factor

The mention of Sherry may conjure images of little old ladies surrounded by dollies sipping from dainty glasses. Or more sinisterly, the fortified wine used to lure Fortunato to his doom in Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” Or perhaps the title girl in a Four Seasons song from 1962. But the distinctive flavor of this tipple from Spain is absolutely vital to the flavor of many of the Scotch whiskies that we drink.

Casks sourced from the Jerez-Xérès-Sherry designation of origin in the southern region of Andalusia are the second most popular vessels (after ex-Bourbon barrels) for aging Scotch whisky. And the results can be exquisite. The containers add an array of tasting notes to Scotch that variously include not only the expected fruits, like black cherry and raisins, but peaches and pears, as well as spice, nuts, herbs, brown sugar, cocoa, leather and—bonus—tobacco.

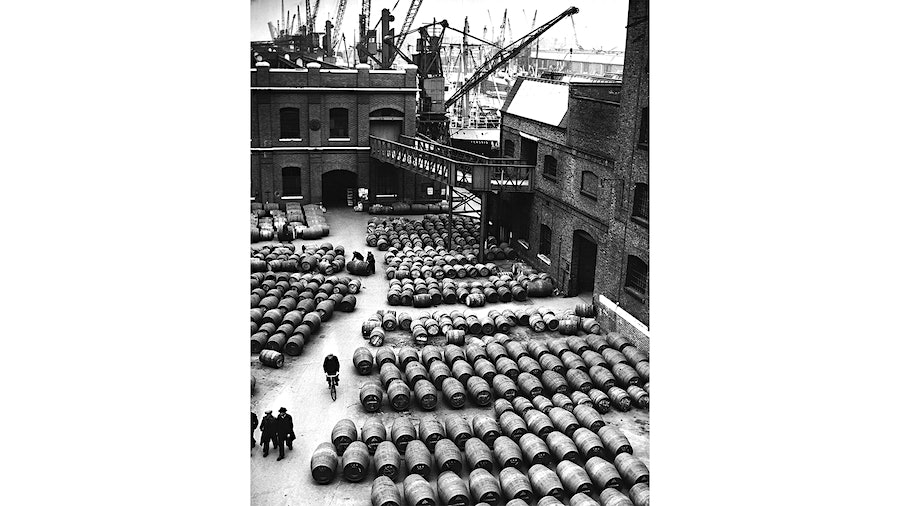

Wooden containers that once held Sherry have long been used by Scotland’s distillers to store their whisky. After all, the United Kingdom has been a voracious consumer of Sherry since the days of Shakespeare. And because the wine arrived unbottled, the casks they came in made handy vessels for keeping whisky. By the end of the 19th century, Scotch makers recognized that they could do more than hold spirits, they could change their character and therefore began being touted as a feature. More recently, the industry Sherry casks have become an exacting tool for treating whisky.

In the 1950s, Macallan, reknowned for its success in making superaged whiskies exclusively in former Sherry casks, began special ordering them. In 1983, The Balvenie master distiller David Stewart debuted a technique that would change not only Scotch maturation, but spirits aging across the board. He created a whisky that now goes by the name Double Wood, by first aging in Bourbon barrels and then transferring the spirit to Sherry casks in a process that is now called finishing. Dr. Bill Lumsden of Glenmorangie soon championed the practice and today it is pervasive in Scotland as well as being used in many other liquors across the globe.

When Dewar’s recently relaunched its single-malt Royal Brackla, it chose to do so with a range of 12-, 18- and 21-year-old releases, all finished in Sherry. “Finishing casks are used to add nuance, additional flavor characteristics so to speak, that would not be found within the initial maturation period,” says the distillery’s malt master Stephanie Macleod. “In the case of Royal Brackla, I chose to showcase different Sherry casks for each expression, so one can explore the individual influence each Sherry has on the finished whisky.”

If you’re thinking about scrounging up some used Sherry casks and simply pouring your Scotch in for a finish, it’s far more complicated than that. First, the containers that are used in the world of Scotch are more properly called “Sherried casks,” made specifically for whisky storage. Lumsden explains that the casks used in actual Sherry production would essentially be useless for whisky making once the winemakers are done with them, with not enough flavor to make an impact. Instead, businesses that store Sherry, such as Bodegas Jose y Miguel Martin, conduct a side business seasoning barrels for Scotland. This is done by filling fresh casks for one to three years, a process that renders the Sherry unfit for sipping. “New oak is used so the wood absolutely kills the wine,” says Lumsden. After that, the would-be Sherry is made into vinegar or brandy.

Don’t bemoan the detoured wine, however. Whisky’s role in the Sherry world has helped shore up an industry that has endured long periods of decline. Even during its current resurgence, says Lumsden, not enough Sherry is being consumed to supply the needs of the spirits industry if it were to source casks actually used for Sherry. “It’s not the most romantic story, but it works wonderfully well for the money.”

Speaking of money, Sherried-casks are an added expense for Scotch makers as they typically go for 1,000 euros apiece. Ex-Bourbon barrels, which perform 90 percent of Scotch aging, are a quarter the cost. Even given that barrels are about half the size of the Sherry containers, called butts, they still offer a considerable savings.

When you’re ready to fork over that kind of dough for your very own sherried butt, there are still decisions to make, primarily the type of wine that seasoned the cask. “Different Sherries will give subtly different flavors,” says Neil Strachan, the U.S. ambassador for The Balvenie, “from a sweet note from a wine like Pedro Ximénez or grassy notes from a dry fino style. The most commonly used is oloroso, as it is the simplest to make.” Another choice, amontillado, falls somewhere between the sweetness of oloroso and dryness of fino.

Even rarer is palo cortado, a sort of mistake of the Sherry world that comes in between oloroso and amontillado in flavoring attributes. Macleod incorporates it in her Royal Brackla 21 year old. “I chose a Sherry trinity of Pedro Ximénez, Palo Cortado and oloroso sherry casks to halo this incredible whisky,” she says. “These finishing casks create a divinely Sherried whisky balancing Sherry, oak and the delicateness of Royal Brackla.”

Another variation is the type of wood used to make the cask, either fine-grained American oak or coarser-grained European oak from Spain. Perhaps surprisingly, the American type dominates in Sherry cask construction. “In the case of American oak, these barrels can offer notes of caramel, coconut and vanilla,” says Strachan. He compares it to European oak, which delivers “notes of dried fruits, spice and pepper.” American oak is more prevalent due to rules on felling oak from Spain, making these casks hard to source. “Luckily, we have an old family relationship to guarantee our supply,” he says. And the casks last for a literal lifetime. “The good news is after we use the cask for the Doublewood’s short finishing, the cask will be used in our stock model for at least 80 years but probably longer.”

Macleod points out other differences. “American oak [with its tighter grain] will take longer to yield its character to the whisky, but when it does it’s packed with vanilla and beautiful color,” she explains. “European oak gives a spicier character and is much faster [typically one to two years] in bestowing the whisky with its character. However, that said, the season in which the casks are put away, the length of time they spend in the cask, their position in the warehouse, the climate . . . can affect the mature spirit.”

Lumsden, on the other hand, says that wood comparison may be moot as he believes 75 percent of the impact comes from the Sherry wine soaked into the staves. Furthermore, there isn’t much in the way of European oak Sherry and he characterizes what there is as porous and leaky.

“I scoff at the claim that you get lots of nuances from the European oak,” he says. “At the point that we finish Lasanta [Glenmorangie’s 12-year-old Sherry-finished malt] it has already been in American oak for 10 years, it’s already taken an awful lot of wood extraction from my ex-Bourbon barrels and I’m just looking for the nuance of flavor that a Sherry cask can give and it gives these very big toffee and raisin and caramel flavors. But they are like wild horses, if you are not careful.”

The thought of the whisky’s flavor seems to distract the good doctor from shop talk, however, and Lumsden begins to ponder what he would do with a stolen moment: “I would sit down and pour myself some Lasanta and light a Montecristo Edmundo.”