Shade in the Dusk

Motorists turning westbound from Interstate 91 onto Connecticut Route 20 near the small town of Windsor witnessed a sight this past June that would break the hearts of agricultural appreciators and cigar enthusiasts alike. For as long as residents can remember, a series of traditional barns used to cure freshly picked Connecticut shade tobacco could be seen from this part of the state highway, a roughly five-mile stretch known as the Bradley Airport Connector. But on this day, the barns were gone—reduced to wood piles.

While locals were surprised, many were not shocked. After all, it’s no secret that the state’s once-bustling shade tobacco industry has taken a sharp turn for the worse in recent years. Countries such as Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua and even Brazil now grow their own variation of Connecticut shade that’s at least on par with the original in terms of quality, if not better if you factor in the lower price. Add in the costly overhead of growing shade in the Upper Connecticut River Valley as well as developers with deep pockets frothing at the mouth to pave over the fields, and one can begin to understand why Connecticut’s shade farmers would be inclined to give up, or switch to another type of crop.

The razed barns actually belonged to O.J. Thrall Inc., one of the oldest farming families in America. Up until recently, the Thralls were the largest growers of golden Connecticut shade wrapper tobacco, which is prized by cigarmakers for its distinct mild flavor and aroma that complements and rounds out almost all types of tobaccos in a blend.

“It is one of the cleanest, silkiest smooth and most elegant wrappers in the cigar world,” says Nick Melillo, owner of Foundation Cigar Co. Melillo grew up in the Valley, his company is headquartered there and he uses shade on his Charter Oak CT Shade brand. “Connecticut shade’s vein and cellular structure are very thin compared to many other seed varieties, such as Cuban seed. Due to the nature of the leaf, it is like the icing on the cake; it really enables the blender to display the filler tobaccos and the wrapper puts the finishing touches on the binder tobacco. The aroma and flavor is pleasant, smooth and mild.”

The Thrall’s biggest customer was General Cigar Co., whose Connecticut shade varieties include such popular brands as Macanudo and Hoyo de Monterrey Excalibur. A little over two years ago, the Thralls decided that growing shade tobacco was no longer economically viable. Now they only grow Connecticut broadleaf, a genetically different plant that grows in the open sunlight and is used to make dark, maduro cigars. (Broadleaf, unlike shade, is actually enjoying a bit of an uptick this year.) The company announced plans in 2017 to sell around 325 acres of land they once used for shade tobacco in Windsor and nearby Windsor Locks. That year, a 67-acre plot of premium farmland was put up for sale at $13.5 million; a nearly 22-acre field nearby was being advertised for $2.4 million; and another 27-acre parcel commanded a price of $3.37 million. In an area where the average income is around $37,000, that’s big money.

The 76 acres along Route 20 where the razed barns were located—about two and a half hours north of Manhattan—already appear poised for transformation. In May, Windsor Locks residents voted to approve plans for the construction of a brand new $213 million sports and entertainment complex that is slated to offer a host of amenities, including a 5,500-seat outdoor soccer stadium. Developer JABS Sports Management has also promised nearly 400 jobs (with at least 86 to be filled by Windsor Locks residents), as well as an estimated $15 million boost in local spending in its first year of operation.

This pressure to develop Connecticut’s best farmland into industrial and commercial zones is immense, but not new. In fact, part of the reason Interstate 91 was built in the 1960s was to boost urban renewal along the Connecticut River’s “low value” waterfront. Three lanes in both directions, I-91 begins in New Haven and stays close to the Connecticut River as it bisects the state and connects larger cities such as Hartford to Springfield, Massachusetts, before continuing up through Vermont and ending at the Canadian border. In the Valley, it is common to see vibrant tobacco fields of Connecticut broadleaf, Havana and shade next to housing developments and shopping centers. This includes areas around Windsor and extends north to Southwick, Massachusetts.

Unfortunately, the best farmland is also usually the most tantalizing for developers. And the Upper Connecticut River Valley where shade is grown is ripe with “some of the best agricultural soils in the Northeast,” according to Dr. James LaMondia, chief scientist for The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, or CAES. Established in 1875 as the first laboratory of its kind, CAES works closely with all types of farmers to conduct scientific research in agriculture to increase crop yields and boost resistance to disease and pests. It was here that the famous Connecticut shade seed, after years of crossbreeding with the Havana-, broadleaf- and Sumatra-seed varietals, was developed for its release in 1910. LaMondia works to breed new types of shade seeds that are resistant not only to blue mold, which can destroy 100 percent of a crop in a year, but also to tobacco cyst nematode, a nasty little parasite that feeds on the plant’s roots.

The Windsor series of soils in the Valley consists of mostly permeable sand that drains water excessively fast. “The soils here are fantastic,” says LaMondia, who’s been studying tobacco out of the Windsor office of CAES since 1987. “I’ve worked in other places where you go to take a soil sample and you have to try three or four times to be able to get down six inches without hitting rocks. Here they just don’t exist. In many places you can’t find a rock.” Glaciers are the reason: the land once sat at the bottom of Lake Hitchcock, a glacial lake that formed when the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated back to the Arctic some 15,000 years ago.

The topsoil here is not measured in inches, but in feet. Shade tobacco plants thrive in this kind of sandy, well-aerated and well-drained soil because it can set its roots down deep. If the soil gets too muddy, though, shade plants are likely to develop root problems. “Tobacco doesn’t like wet feet,” says LaMondia. The fine sand leeches rainwater away and, combined with a microclimate of periodic rains and hot, humid summers, creates ideal conditions for growing tobacco.

The microclimate and quality of the Valley’s soil is one of the main reasons why colonists first settled the area in 1633. The settlers saw Mohawk Indians collecting and smoking wild, native tobacco that naturally grew along the river. The Mohawks taught the settlers how to cultivate the plant, and by 1640, a type of tobacco varietal called shoestring was being sent along trade routes down the Connecticut River as a cash crop, used to purchase items that could not be produced on a farm as well as pay taxes.

A mid-1600s law that prohibited Connecticut residents from using tobacco grown outside the state created the area’s first boom. Most of the tobacco at this time was either being chewed or smoked in a pipe, but by the early 1800s, consumers began shifting to cigars. Broadleaf and Havana varietals were introduced to the region, where they flourished. Around the turn of the 20th century, a new type of tobacco called Sumatra started appearing in the United States, and the seed varietal was soon being grown in Florida. Tobacco growers in Connecticut knew it would disrupt their market. In response, Connecticut farmers began growing their own version of Sumatra around 1900. They erected elaborate tents made of cheesecloth affixed to cedar posts to mimic the shady growing conditions of Sumatra, an island in modern-day Indonesia. The test crops exceeded expectations, and in turn scientists bred a new tobacco seed that would thrive in such fields. Connecticut shade was born.

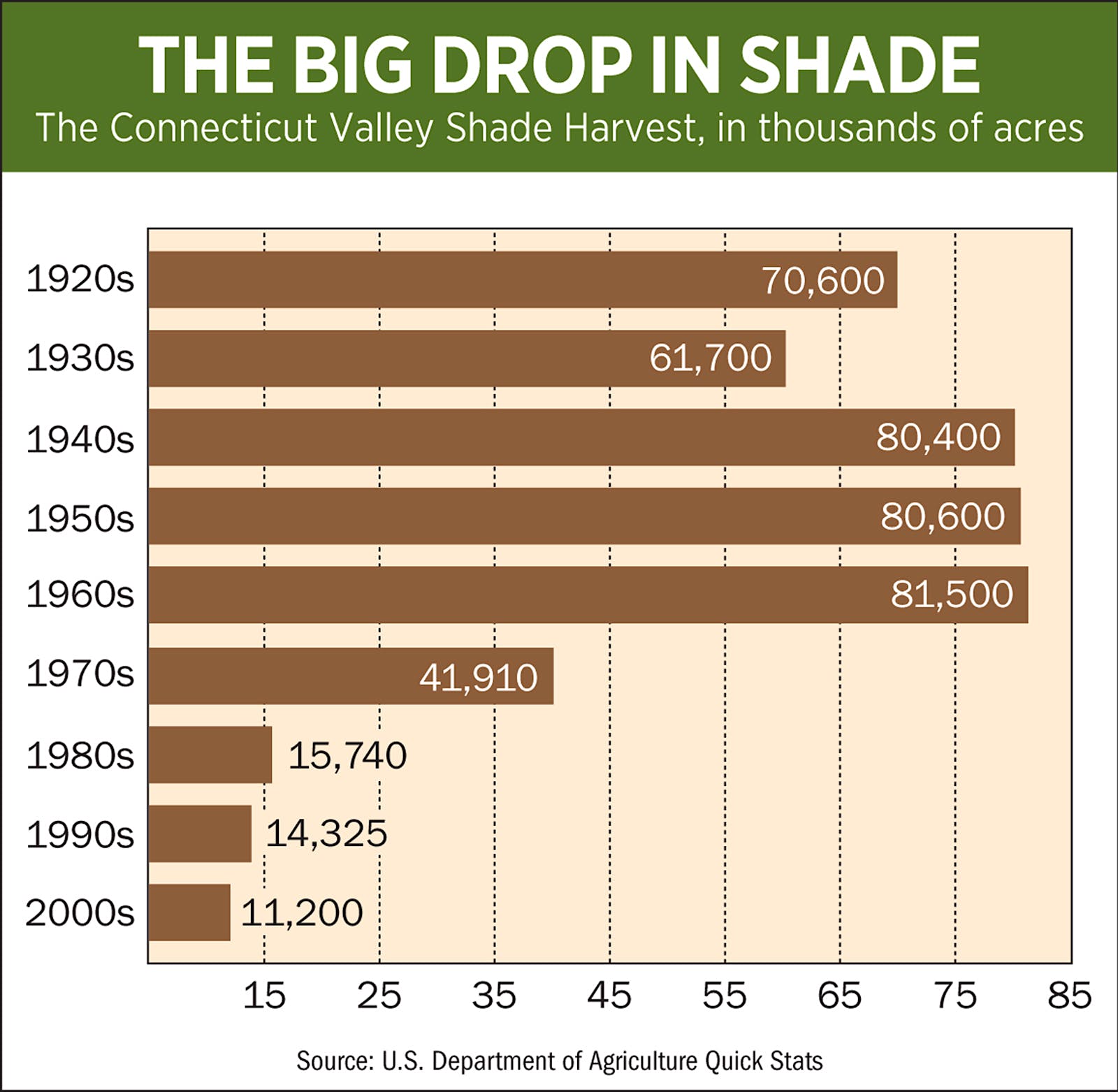

Around 1910, the Connecticut shade seed was released to farmers, and the results were spectacular. The new shade had smaller veins than broadleaf, which meant more cigars could be rolled from a single leaf. Shade was also thinner and more pliable, while offering a soft, velvety feel that customers adored. When cured and aged, the green leaf turned into an attractive, golden brown loaded with oils. By 1921, nearly 8,000 acres of genuine, Connecticut shade was harvested in the Valley. More importantly for farmers, shade sold for the highest price per pound compared to any other tobacco grown in the United States.

In the 1940s, annual harvests averaged about 8,800 acres. These high numbers continued through the 1950s, but by the ’60s and ’70s plantings began to slide. Labor costs rose, pushing many of the smaller growers to switch to less expensive crops; others couldn’t resist the developers, and sold their land. By 1979, only 2,720 acres of shade were harvested in total by Valley farmers. Two years later, Consolidated Cigar (now Altadis U.S.A.), once a major grower of Connecticut shade, pulled out as it moved to homogenized sheet wrapper for its mass-market, machine-made cigars. Though Altadis returned to the Valley in 1998, its shade acreage was nowhere near what it used to grow. And while there were small upticks in the late 1990s and in 2012, plantings in the valley continued to decline to the point that shade crop statistics are no longer kept by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Today, the only major shade growers left in the Valley are Altadis Shade Co., located in Somers, Connecticut, and the farmers who make up Windsor Shade Tobacco Co., who grow on the west side of the Connecticut River. Jean-Marc Bade, general manager of Windsor Shade since 1989, oversees the sorting, grading and baling of Connecticut shade for buyers. Established in 1937 as a cooperative to pool resources and boost stability, Windsor Shade has only three members: Dwight Arnold Farms Inc. and S. Arnold & Co., both in Southwick, and the Markowski Farms in West Suffield, Connecticut. It once had 10 members, including the Thralls.

It’s a hazy, muggy morning in August in the Connecticut River Valley. It’s tough to see farmland past the car dealerships, shopping centers and housing developments, but a visitor can spot the gently rolling hills and loamy soil if he knows where to look. Save for an 18-hole golf course, the area near S. Arnold & Co. has managed to remain relatively free from development.

“This year, the weather has been near perfect,” says owner Stewart Arnold. A gruff, no-nonsense type of a guy, Arnold says the weather has been largely hot and humid, ideal conditions to grow full, healthy tobacco plants. “I can always add water,” says Arnold, a third-generation grower. “But it’s impossible to take away.” Arnold is only growing about 15 acres of shade this year, down from 36 acres two years ago. Walking on a dirt road that divides his shade fields, he says that because the demand for shade is down, he’s begun growing broadleaf in order to make a profit. This year, he planted 40 acres, and already he has a buyer.

As he speaks, his son Seth, 28, drives around in a truck to pick up plastic totes resembling postal boxes that the field workers are busily filling with beautiful shade leaves. Each leaf is laboriously picked one by one. Soon after, the leaves will be strung together and festooned on long lines or on short tobacco sticks called laths before being hung on the rafters of a wooden curing barn.

Just down the street, Stewart’s brother Donald concurs with the weather report, saying he’s expecting a high-quality crop. Standing among the nine-foot-tall shade plants, some poking into the nylon netting, Dwight dodges field workers as he speaks in short sentences, with an avuncular side grin. He’s growing about 25 acres of shade this year, down a little from 2018. But he remains optimistic that much of it will be wrapper grade, which can range in price from $45 to $50 per pound. And like his brother, Dwight has also diverged into broadleaf and has planted about 40 acres this year.

Brothers Ed and John Markowski, owners of Markowski Farms, are no strangers to broadleaf. The family farm actually started out growing the varietal and then in 1989 they started planting shade “because it was in demand at the time,” says Ed. Tall with square shoulders, Ed says that they’ve dedicated about 250 acres of their fields to broadleaf and about 60 acres to shade. While he wishes to see the demand for shade pick back up, he isn’t optimistic.

The modern cigar smoker, though, is not looking to smoke the milder cigars that Connecticut shade typically covers. Instead he wants something stronger.

Looking at the Cigar Aficionado and Cigar Insider tasting database, which is a barometer of yearly trends in the humidor, one can clearly see demand has fallen for this type of wrapper. In the first issue of the magazine, published in Autumn 1992, nine of the 17 non-Cuban cigars rated—53 percent—were covered in Connecticut shade. In 1998, we rated 192 cigars made with shade, 21 percent of the total cigars we reviewed that year. And in 2018, we only rated 25 cigars made with shade, a mere 3.2 percent of the total.

All three of the farmers say that high overhead is the major problem of farming tobacco the Valley. Everything needed to sustain a shade farm—from the cedar posts, to the imported nylon netting and the tobacco barns—simply costs more here. Labor, too. At one point in time, area teenagers worked the field for summer jobs. And while each of these co-op farmers still has a few teenagers on the seasonal workforce, the majority are brought in from Jamaica and Puerto Rico. The workers are provided housing and are paid around $14 an hour. For comparison, workers in Ecuador, which grows its own version of Connecticut shade, do the same job but get paid a little over $3 per hour.

Curing barns also run high in the States. Building a new barn in the Valley can run between $100,000 to $230,000. Each of the farmers noted that lack of space to properly cure is one reason they hold back on planting more acres of shade. All total, the cost to build and maintain a working shade tobacco farm ranges from $30,000 to $40,000 per acre. Competition from countries such as Ecuador, Honduras and Nicaragua, which all grow their own versions of Connecticut shade, is also a major problem. Not necessarily for wrapper, but for shade that falls into the binder and filler grade category and will end up on machine-made cigars. The lower grades from Connecticut are considerably more expensive than from other countries.

“The farmers [in Connecticut] have to sell every leaf. Every. Leaf,” repeats Rich Dolak, the Connecticut tobacco buyer for both Arturo Fuente and J.C. Newman for the last 20 years. “That’s so they can make money. They are in a global market for that lower-grade stuff and they are getting killed. . . . It’s not that the tobacco’s not great. It’s that they are competing globally with these low-cost providers. And they are getting hammered.”

Dolak remembers farms that he once visited that just aren’t there anymore. “When I go up there now, it’s a housing development. I never thought I’d see it in my lifetime, but I’m seeing it. And it’s a shame. I’m shocked. The demise is unbelievable.” He also believes that when General Cigar closed its Connecticut farms in the early 2000s, it was a huge blow to the region. “The valley lost its champion,” says Dolak, who saw the large company as important because they would purchase low-grade tobacco for their own machine-made products.

Ernest Gocaj, who used to oversee those farms and is now the director of tobacco procurement of General Cigar Co., still buys a lot of tobacco from Windsor Shade for use on General’s popular Macanudo Café brand, as well as lower priming leaves (which are lighter) for Macanudo Gold Label. The company also uses Connecticut shade as binder for some of its cigars. “There’s no place in the world you can find the same aroma and taste,” says Gocaj. “Hopefully we are never going to get out of the Valley. We are going to stick with shade wrapper forever, unless the growers decide [to stop]. But as long as they grow even five acres, we will buy.”

Dolak, too, says the Fuentes and Newmans will continue to support Windsor Shade. “What we like to remember is that we really are a partnership between the farmer and the manufacturer. Because if you grind a farmer too much, in the end they are going to go out of business and then what do you have? It’s not an unlimited supply. You kind of got to be there for them in the tough years, and they’ll be there for us in a good year.”

Still, some cigarmakers have already switched to versions of Connecticut shade leaf from other countries. Davidoff is perhaps the most famous to make the switch. In 2001, the Dominican cigarmaker changed its signature wrapper on legacy brands such as Davidoff Special R, Aniversario and Grand Cru from Connecticut shade to Ecuador Connecticut. Romeo y Julieta Vintage also moved to Ecuador in the mid-2000s, as well as the La Gloria Cubana Wavell Maduro.

Connecticut-seed tobacco grown in Ecuador is quite similar in appearance and flavor to Connecticut shade, but the leaf is grown in the open sunlight, rather than under shade tenting. The near-constant cloud cover in the region of Ecuador where the tobacco is grown negates the need for shade, reducing cost. Many cigarmakers say the same thing about Ecuador Connecticut: it’s cheaper and more consistent than genuine Connecticut shade.

Bade says that the co-op has taken some actions to help cut costs. At one time the sorting and grading was done in Connecticut, but now it’s done in a facility in Santiago, Dominican Republic. The building was once owned by the co-op but ASP Enterprises Inc., which cultivates Connecticut-seed wrapper in Ecuador, bought the facility, now called ASP Santiago, in April 2013 after the co-op’s volume began to drop. According to David Perez, president and CEO of ASP Enterprises, Windsor Shade will “use the facility for three to four months or whatever time they need to sort their tobacco, and I use it the other months of the year. It’s a very friendly atmosphere.”

While Bade and the Windsor Shade farmers toeing the Connecticut shade line understand that the market is shifting away from shade, they still believe in the crop. “We’ve always focused on quality, but more than ever, our market is the premium market,” says Bade. “We just have to work on growing the best tobacco we can.”