Quest For The Best

At the end of 1984, I confronted an annual task that most film critics face: my year-end list of the 10 best (and worst) films of the year. In a year that included The Killing Fields, A Passage to India, Amadeus and Places in the Heart, not to mention Splash, Ghostbusters and Beverly Hills Cop, I chose Rob Reiner’s mockumentary, This Is Spinal Tap. For my trouble, I received some notoriety of my own: a place on the local list of “Year’s Most Boring People.”

It’s dicey enough to anoint a winner from a single season, but for professional critics and film buffs alike, naming a greatest film of all time is terrifying. The criteria are so hazy. Does it mean your favorite movie, the one you watch over and over? Or should it be an arthouse flick, the one that appeals to cinephiles? Are there no time parameters? Or do contemporary films belong next to the classics of old?

And the task keeps getting harder. As the sheer number of movies rises exponentially and the ways in which we view them changes, the foundation on which they are rated constantly shifts.

The latest brouhaha concerning the perennial question sprang up with Sight and Sound magazine’s 2022 poll, which asked critics to name the greatest films of all time. Controversy arose because after 60 years in which Citizen Kane ruled the list, the 2022 poll had plopped an obscure Belgian art film from the mid-1970s called Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles into the No. 1 slot.

I will confess that, as hard as I’ve tried, I have never been able to sit through Jeanne Dielman. It’s an experimental, three-hour-plus film about the mundane chores of a single mother, who happens to be a sex worker in the afternoon. I’ve never lasted more than an hour. And it’s not that I object to long films: I sat through Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman three times—gladly. So how did this film leapfrog from 35th place (its first appearance on the list, which came in 2012) all the way to No. 1? Did something occur which suddenly diminished the greatness of Citizen Kane and put a spotlight on the previously undiscovered charms of Jeanne Dielman?

Of course not. What that poll revealed was not a drastic shift in the quality of the movies but, rather, a tectonic generational upheaval in film critics that’s been brewing for 20 years.

But the poll also raised a larger question: who gets to decide which films are truly the greatest? Movies are only a little over 100 years old. Until the turn of this century, seeing a movie meant being part of an audience in a crowded picture palace, experiencing moving pictures communally. (Talk about old school.) Just as the baby-boom generation of critics and their elders—most of whom worked at legacy media publications—began to die, retire or be laid off, the Internet roared to media dominance. With it was created a burgeoning generation of arbiters who view movies on alternative formats and assess them online rather than in print.

Discounting special-effects extravaganzas, franchise tentpoles and comic-book films, the still-to-be-made classics are destined to find their life via streaming. But why would a younger and expanding (145 critics in 2002 versus 1,639 in 2022) slate of voters rally behind an obscure art film that hadn’t been in circulation in the United States for 30 years? How did they even find it? The answer is the technology. The number of titles available at the click of a mouse or a remote control is far greater than at any time in history. In the same way that baby boomers rediscovered films like Casablanca thanks to the late show in their youth and championed the classic status of those films, younger critics claimed Jeanne Dielman as their own.

When I came of age as a would-be film critic in the 1960s and early 1970s, just seeing movies took monumental effort. In high school, I loved film and tried to see everything that even vaguely caught my interest. My high-school grades suffered because I would spend weeknights haunting the handful of theaters in my native Minneapolis that played the trickle of arthouse fare that reached the flyover. In my senior year of high school, I saw Sidney Lumet’s Bye Bye Braverman multiple times in the single week of 1968 it played at the Suburban World theater in

Minneapolis. George Segal, the film’s star, was one of my favorite actors of the period and this film seemed like a window into another world—an intellectual New York Jewish world that seemed both very witty and extremely exotic compared to my nebbishy midwestern existence.

Almost 50 years later, I interviewed Segal when he received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. I took the opportunity to express my fondness for Braverman, telling him I’d seen it three times the week it played Minneapolis. His surprised reply was: “Bye Bye Braverman played in Minneapolis?”

Exactly. Back then, I knew that if I didn’t see it right then, I might never see it at all. Once a movie was out of theaters in the 1950s and 1960s, it could be years before it was shown on television. In the days before home video, you never knew when some old film you’d heard about but never seen would turn up on TV. So you had to be a detective, scouring TV Guide’s movie listings or checking local revival theaters.

As film historian Leonard Maltin told me, “When I was in junior high, I would set my alarm clock for 2:20 a.m. Then I’d wake up and go to my parents’ TV in the living room and turn it on to watch the late, late, late show so I could see Howard Hawks’s Twentieth Century.”

I spent most of the 1970s writing movie reviews for newspapers in small midwestern towns, but the movies that came to my town during this incredibly fertile time in movies represented only a fraction of the films I was reading about in more urbane publications. I may not have been able to see them, but I certainly knew what those movies were. I had an insatiable appetite for films. I wanted to see everything that was out there.

Even then, the definition of a classic film was a slippery thing. With so much more cinema available has it become more elusive? I spoke with several critical colleagues, as well as historians and filmmakers, about how films earn that mantle of “classic” and the answers had a surprising similarity, echoing Maltin, who said, “A classic is a film that’s stood the test of time and stands up to repeated viewings.”

But what if that favorite film is a piece of forgettable commercial crap, remembered fondly by a mass audience from an undiscriminating youth? As adults, those former teens still watch those movies repeatedly and pass that affection along to their children. By Maltin’s assessment, such films as Porky’s might qualify as classics. But are they? Really?

“Everyone has their own definition,” Maltin admits.

Joshua Rothkopf, former film editor of Entertainment Weekly and Time Out New York, says, “What is a classic is rooted to your idea of taste and where taste comes from as you get older. People younger than me tell me they think Star Wars is a classic. It makes me cringe, in the same way other people might cringe if I call a John Carpenter horror film a classic.”

In a half-century of reviewing films, I probably saw an average of 150 to 200 movies a year. I have a memory which, in the case of a surprising number of films, can recall the specific theater and details about where I saw it. A quick example: The first time I saw Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs was a 10:30 p.m. screening at the 1992 Toronto Film Festival at a now-demolished theater. I was exhausted because this was my seventh movie of the day. Then the movie started—and by the end, I was so juiced that I was ready to watch seven more. I still recall being a pre-teen seeing Lawrence of Arabia and how I stood in the drinking-fountain line at intermission, parched from spending more than two hours in the desert with Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif.

The point is that something about watching an epic film in a big theater leaves you in a dream state, as though you’ve spent a few hours living inside another reality. Moments like those cannot be duplicated at home or simulated through virtual reality. And without them, how has our concept of a great movie changed?

While it is easy to get caught up in a movie at home on the big-screen TV—and to maintain the discipline to watch it all the way through, without a pause for snacks—I’ve never had the otherworldly experience at home that I get in a movie theater.

By making lists—regardless of how they are screened—critics try to shine a spotlight on what they consider the greatest films. It’s a way to help viewers find a path through the massive thicket of that content, creating a body of work, which offers a starting point to begin that hunt. The Sight and Sound 2022 controversy draws attention to an entire list of titles outside the traditional canon, films people might not otherwise be aware of.

Still, you come back to the question of defining terms. When critics make choices for a poll ballot, or publish a year-end list of best films, are they choosing the films they think are best, or the films they like the most?

Paul Schrader, filmmaker, screenwriter (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and former critic, told me, “Personally, I like the discipline of a Top 10. It forces one to re-evaluate and kill some of your babies—or at the least send them to the second floor.”

Manohla Dargis, film critic for The New York Times, said, “All I can do is pull from my favorites. My favorite changes, day to day. Today, it might be The Wizard of Oz and tomorrow it might be Jules & Jim. Or There Will Be Blood. Or it might be a Singin’ in the Rain day.”

As a critic, when it came to making lists, I focused on a handful of factors that made films my favorites: Did it move me? Did it entertain me? Did the movie make me think about it afterward? Have my feelings for the film deepened with repeat viewings? If I’m flipping channels and happen on this film, will I stop flipping and stay with it? Do I see new things when I watch it again? Did it do something that moved the needle in the art of cinema, while still compelling my interest? (I know; it’s a real nerd question.)

Critic and film historian Molly Haskell told me she often introduces films by noting the difference between her favorites and what she considers great films: “It’s a unique film that fits those two categories,” she said. “That’s one reason there’s so much confusion. A perfect film doesn’t interest me. Welles’ Magnificent Ambersons is deeply flawed, but it’s still a great, great film.”

Covid may have shrunk the number of theaters and multiplexes able to make it financially. But production only seems to be expanding as the number of streaming outlets grows. The future points to more movies destined for smaller screens. The complaint that multiplex screens are dominated by Hollywood blockbusters with $200-million-plus budgets isn’t a new one. Independent films, foreign films and documentaries may be the kind of movies that win awards, but those movies were destined to shrink the day the first teenager discovered he could watch video on his smartphone.

Yet audiences came out to theaters in throngs for Top Gun: Maverick, Avatar: The Way of Water and Elvis, (all of them Oscar nominees), and, more recently, John Wick: Chapter 4, which raked in nearly a quarter of a billion dollars worldwide in less than two weeks. At some point, an arthouse hit will break through in theaters and change the game again. Or not.

At the point when I retired from writing reviews a half-dozen years ago, I already felt the time crunch created by the breadth of content available. It might seem easy enough when movie publicists say, “Could I send you a link to watch it?” But access wasn’t the issue—time was. I would inevitably joke, “Can you also send me the two hours I’ll need to watch it?”

My younger colleagues feel it even more acutely, now that films that stream without ever playing in theaters have become events in themselves, forcing critical consideration. “I worry about that all the time,” says Alison Wilmore, film critic for New York magazine. “I fret that some great small thing will pass me by. But there’s no way to even come close to seeing everything.” And, because the pool of films continues to increase, says Rolling Stone critic David Fear, “It’s become more difficult to recognize a masterpiece in our midst.”

As the saying goes, the cream rises. The search for the next classic goes on, along with the ever-shifting tastes and opinions that accompany it. So the question becomes: A century from now, which films will we still be carrying a torch for?

Jeanine Basinger, who created the film studies program at Wesleyan University, may shake her head in dismay at the selection of Jeanne Dielman (“A film made for a classroom, not a movie theater,” she told me). But she can’t condemn the discussion it ignites: “What’s good about [its selection as No.1] is that it makes people stop and think about films. That’s never a bad thing. It means the art form is alive.”

“People think of movies as entertainment,” Basinger says. “Yet cinema is an art form. This is a mass-entertainment art form that everybody goes to.”

Director John Landis told me that people who read the lists may not appreciate just what a miraculous thing it is that any movie gets made, let alone turns into a classic. Given the effort of coordinating the myriad people and skills it takes to assemble one, “movies are alchemy,” he said.

In that spirit, I humbly submit my choices for best films.

...

I spent the better part of 50 years as a movie critic and, if you ask me to name the greatest movies in any specific category—greatest car chases, funniest movies, best thrillers with a twist—I can instantly summon titles because these are finite lists, to my way of thinking. Yet, asked to assemble a list of my Top 10 films of all time and the huge universe that opens creates instant confusion.

As I considered the many films I’ve loved and admired over the years, I finally landed on a selection that fit several criteria: They had to be movies I loved; they had to be movies I’ve watched repeatedly and love more each time; they had to be movies I unreservedly recommend to other people. In other words, the kind of movies that I stick with, if I find them while switching channels, no matter what else I’m doing or how far into the movie it is.

I list these in no particular order because, on any given day, that order (and, perhaps, even some of the titles) would change.

1 - The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather: Part II (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola’s first two Godfather films are as rich and involving as great literature–Shakespearean in their themes of family, ambition, betrayal and venality; filmed like a Rembrandt painting; filled with acting for the ages—they are gripping accomplishments in cinematic storytelling.

2 - Chinatown (1974)

Roman Polanski’s ’30s-era detective story is the perfect film noir: the story of a man with a fatal flaw who falls for a woman who exploits it. Polanski’s taut, glossy direction and Robert Towne’s razor-sharp script blend with career performances by Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway.

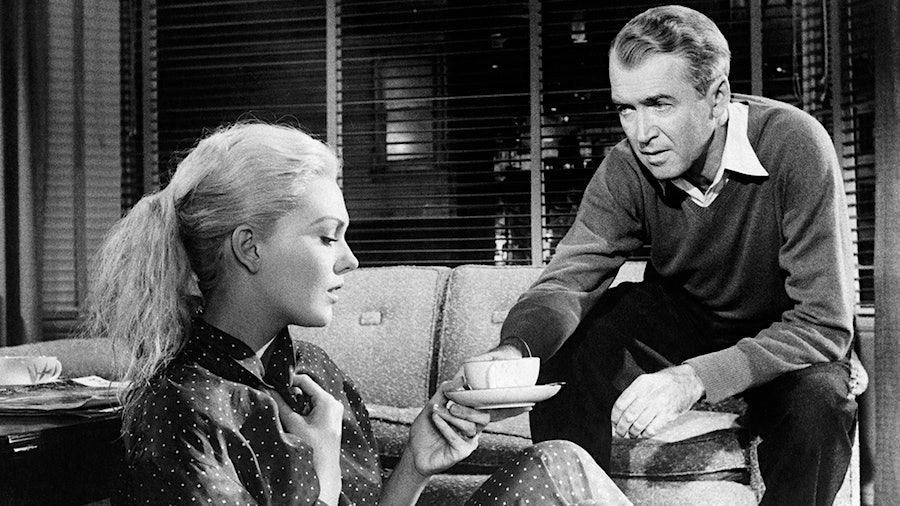

3 - Vertigo (1958)

This thriller is one of three films on this list about impossible love. While modern viewers may find it dated at times, stick with it, as Hitchcock keeps pulling the rug out from under a heights-phobic James Stewart in his pursuit of dream girl Kim Novak.

4 - The Wild Bunch (1969)

While I feel almost as strongly about John Ford’s The Searchers, I have an even longer attachment to this Sam Peckinpah epic about bad men whose personal code has outlived its time, with an amazingly bloody final gun battle.

5 - Casablanca (1942)

The best romantic dramas end unhappily, and this is Exhibit A: a World War II romance of impossible love involving Nazi spies. This is a romantic triangle, whose most important components are played by Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.

6 - Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

I think of this as an intimate epic, the kind of compelling drama and panoramic sweep that only computers can reproduce today, with Peter O’Toole in a riveting performance and a story that crosses continents.

7 - Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

Ang Lee’s deceptively romantic martial-arts drama stars Chow Yun-Fat and newly crowned Oscar-winner Michele Yeoh in fantastic scenes of fighting and flying. Its ending always makes me cry.

8 - E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Steven Spielberg blended a sharp eye for pop culture with a sense of childlike wonder, using state-of-the-art effects of the time to amplify his mastery of creating tension, comedy and heartfelt emotion in the story of a visitor from another planet.

9 - Citizen Kane (1941)

This is the gold standard—Orson Welles’ story of the rise and fall of a media baron who thinks his money should be able to buy him political power. Eighty years after its release, it still feels incredibly modern.

10 - Duck Soup (1933) and Best in Show (2000)

Sorry, I can’t choose. I always laugh at the anarchic speed and wit of the Marx Brothers. Best in Show is Christopher Guest’s hilarious faux documentary, set behind the scenes of a prestigious national dog show.