Plugging The Embargo Loophole

Only a month after John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, in February 1961, the new president asked his Secretary of State for recommendations on instituting a “full embargo” against Cuba. In an effort to undermine Cuba’s revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro, Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had already terminated U.S. exports to Cuba and cut imports of Cuban sugar. Now, Kennedy wanted to know if an embargo on all Cuban imports would “make things more difficult for Castro,” and “be in the public interest?”

“The principal items still imported from Cuba are tobacco, molasses and fresh fruits and vegetables,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk responded in a secret report. But a full trade embargo would particularly affect Cuban cigars. “About five million dollars’ worth of high-quality cigars were imported from Cuba in 1960,” Rusk informed the President. “An embargo on Cuban cigars would result in considerable inconvenience to United States consumers,” he wrote, “as cigars of comparable quality could not be obtained from other sources.”

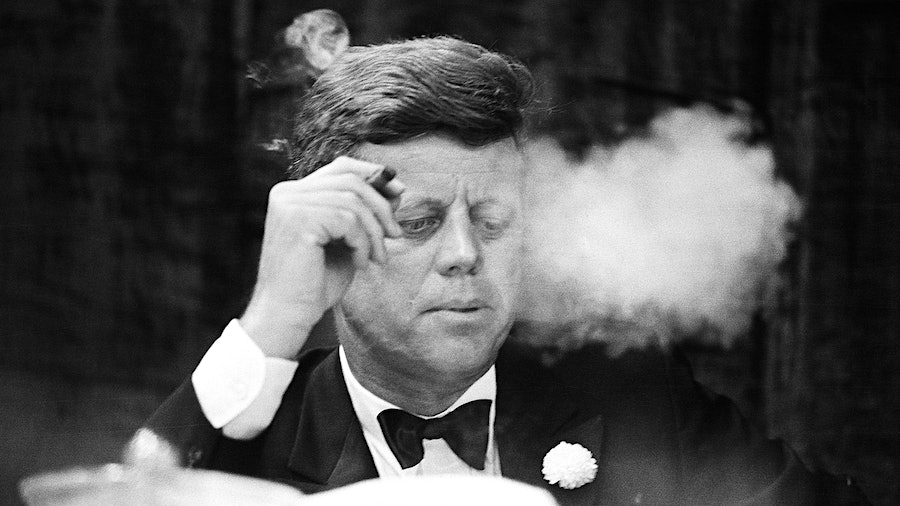

JFK was, conceivably, the most famous of those consumers. As he prepared to issue his presidential directive, “Embargo on All Trade with Cuba,” Kennedy heeded Rusk’s warning. The President quietly dispatched his press secretary, Pierre Salinger, to acquire a stash of Kennedy’s favorite Cuban smokes: H. Upmann Petit Upmanns, 4 1/2 inches long by 36 ring gauge. After Salinger informed the President he had managed to purchase 1,200 of the Cuban cigars, he reported that Kennedy smiled and opened his desk. “He took out a long paper which he immediately signed,” Salinger later wrote. “It was the decree banning all Cuban products from the United States. Cuban cigars were now illegal in our country.”

In fact, only Cuban cigars from Cuba were illegal. Cigars made from Cuban tobacco but rolled in other countries continued to be legally imported into the United States—much to the consternation of the U.S. cigar industry, which no longer had access to coveted Cuban tobacco that was banned under the new embargo. As cigars made with Cuban tobacco continued to enter the U.S. market for purchase by discerning cigar aficionados, they became the catalyst for the first major effort to expand and tighten the newly established U.S. trade embargo against Cuba—creating the broad-reaching restrictions that continue to keep such cigars off-limits in the United States to this day.

The Trade Embargo

Kennedy’s full embargo on Cuba turned 60 this year, but it evolved from a decision by the Eisenhower administration in the spring of 1960 that the United States could not coexist with the fiery and uncontrollable Fidel Castro, and would seek—covertly, diplomatically and economically—to roll back the Cuban revolution. On March 17, 1960, President Eisenhower approved a top secret CIA proposal to develop a covert program to “bring about the replacement of the Castro regime with one more devoted to the true interests of the Cuban people and more acceptable to the U.S.”—a program that would culminate 13 months later with the paramilitary invasion at the Bay of Pigs.

The challenge for U.S. policy makers was the popularity of Castro’s improbable revolution among the Cuban people. “The majority of Cubans support Castro,” Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Lester Mallory pointed out in a secret memorandum in April 1960. Since there was no effective opposition against him, the only way to undercut Castro’s support was through economic hardship. Mallory recommended that “every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba,” including punitive actions to deny “money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and the overthrow of [the] government.”

The Eisenhower administration turned to incremental trade sanctions to weaken the appeal of the revolution. After Castro nationalized U.S. petroleum companies for refusing to refine Soviet oil, Eisenhower cut off Cuban sugar exports to the United States. After more nationalizations of U.S. businesses on the island, and only weeks before the 1960 presidential election, Eisenhower announced a ban of all U.S. exports to Cuba (exempting food and medicine on humanitarian grounds). When President Kennedy succeeded Eisenhower in January 1961, a partial U.S. economic embargo was already in place against Cuba.

The new president faced almost immediate political pressure, particularly from hardline politicians from Florida, to levy a full trade blockade against the island nation. “The situation demands such an embargo,” Congressman Dante Fascell urged Kennedy in March 1961, “and I trust an Executive Order can be immediately issued to place it in effect.” But with the CIA-led invasion of Cuba looming, Kennedy held off. Following the failed attack, protracted back-channel negotiations with Castro over the fate of the invaders captured at the Bay of Pigs delayed further economic action.

On February 3, 1962, Kennedy issued presidential proclamation 3447, decreeing a full embargo against Cuba. The presidential directive authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to implement the embargo, but also gave him discretion to enforce the new trade sanctions. At 12:01 a.m. on February 7, 1962, the U.S. embargo against Cuba officially went into effect.

A Potential Loophole

Only eight days later, the Tampa Tribune newspaper ran a front-page story, “Cigars From Canada Threat To Embargo.” It quoted Customs officials as stating that “cigars made in Canada with Cuban leaf could be labeled ‘made in Canada’ and sent to the U.S.” Florida’s two senators, George Smathers and Spessard Holland, expressed their outrage at this apparent loophole in the embargo and said they would raise the issue with the White House.

On February 16, President Kennedy’s top legal advisor alerted him to this potential “circumvention of the law.” The embargo clearly prohibited transshipments of Cuban goods through third countries such as Canada and Mexico, White House deputy counsel Myer Feldman reported to Kennedy, but should a cigar made from Cuban leaves be rolled someplace other than Cuba, it could circumvent the law. “If a Cuban raw material, like tobacco, is manufactured into another product, like cigars, it loses its identity as a Cuban product and takes on the identity of the nation in which the product is manufactured,” he wrote, warning that “Cuban tobacco can be shipped into the United States without violating the embargo.”

To address this circumvention, the embargo directive would have to be amended—under the Trading with the Enemy Act, which would allow the President to extend sanctions to cover third countries. But this created a possible diplomatic problem—offending longstanding allies and trading partners by implying they were an enemy and impeding their international commercial practices. “The State Department feels that it would be a mistake to do this until they have had an opportunity to seek the voluntary aid of Canada and Mexico in preventing this evasion of our laws,” Feldman informed President Kennedy. “However, if the discussions are unsuccessful, and if it appears that Cuban products will enter the United States by this means, we should amend the proclamation immediately.”

The Treasury Department, which had jurisdiction over regulating and enforcing the embargo, took a different approach. In response to the flurry of questions about what goods were embargoed and what were not, Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a clarification: “Any and all goods processed or manufactured from Cuban imports in a country considered friendly (or at least neutral) may be imported into this country,” specifying “goods, including cigars, made from imports from Cuba.”

The OFAC ruling generated a major outcry from the American cigar industry, which at the time was centered in Tampa, Florida. There, both large and small manufacturers had been jolted by the embargo, which cut off about $27 million in annual imports of Cuban tobacco used to produce premium cigars for the domestic market. Hundreds of Tampa cigar factory workers had already lost their jobs. Now, American cigar producers faced the prospect of having to compete with cigars containing Cuban tobacco. “This ruling has caused great consternation in the industry,” announced the Cigar Manufacturers Association of America.

The Association and its supporters quickly mounted a major lobbying campaign to force the Kennedy administration to redress its decision. On February 27, the board of the Cigar Manufacturers Association passed a unanimous resolution condemning what it called “back door transactions with Cuba contrary to the spirit and intent” of the embargo, and urging President Kennedy to make the trade sanctions “be total in effect.” In early March, the Association distributed the resolution to various senators and congressmen, with a cover letter describing the adverse impact of the embargo “in its present form” on cigar manufacturers, factory workers and consumers, and calling on Congress “to close all avenues of direct and indirect trading with Cuba.” On March 12, Florida Congressman William Cramer introduced legislation to, as he put it, “plug the glaring and gaping loophole in the administration’s embargo.” As a result of the OFAC ruling, “the people of my district lose their jobs,” Rep. Cramer asserted, “and Castro still gets his dollars.”

With his department under political attack for the OFAC ruling, Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon was forced to address these problems. On March 21, 1962, Dillon submitted a lengthy memorandum to President Kennedy to acquaint him with “the difficulties the Treasury is encountering in administering the embargo on Cuban imports,” particularly “cigars manufactured in third countries with Cuban tobacco.”

Those cigars were flowing into the U.S. market at an escalating pace, according to Dillon, who noted a particular surge in cigars made with Cuban tobacco in the Canary Islands. In the previous two weeks, he said, some 146,000 cigars made with Cuban tobacco had been shipped to the U.S. from the Canary Islands, compared with just 10,500 such cigars imported for all of 1961. That wasn’t the only country. “In the last two weeks some 50,000 cigars apparently made of Cuban tobacco were imported from Mexico, while the 1961 import total from Mexico was only 6,000,” he wrote. The significant increase in imports, Dillon

suggested, was “in large part attributable to [the embargo].”

Nor was this “import problem” limited to only cigars. Tobacco brokers wanted to import Cuban leaf that had been processed outside of Cuba. No regulatory authority existed to block such imports. “It may well be that some of these tobacco products are not within the scope of the present embargo,” Dillon warned the President.

“Congress is growing restive about the cigar problem,” Dillon advised, bringing the president up to date on the pressure from key senators, congressmen, the Cigar Manufacturers Association and even the Tampa City Council. The State and Treasury Departments responded to these protests by affirming that “it is the administration’s intent to act promptly if it develops that cigars made with Cuban tobacco are being imported.” In reality, Dillon admitted to Kennedy, under the present regulations, the administration “cannot prevent the daily irritation that comes from admitting cigars legally entitled to entry.”

The Treasury Secretary outlined several options. “We could prohibit imports solely of tobacco products, e.g. cigars,” Dillon told Kennedy. “This would deal with the most pressing problem at hand.” But other issues with the embargo would remain—the import of other commodities with Cuban components (such as canned pineapple) and even more important, U.S. corporate subsidiaries in third countries doing their own sales to and purchases from Cuba. A second option was to expand the embargo to “prohibit imports not only of tobacco products, but also all goods containing a significant amount of Cuban raw materials.”

President Kennedy approved option two. On March 23, 1962, the Treasury Department announced it was amending the embargo to ban all financial transactions relating to the importation of merchandise “made or derived in whole or in part of any article which is the growth, produce or manufacture of Cuba.” In a story titled “Leak in Embargo on Cuba Closed,” The New York Times reported that “officials said the tightening of the embargo was aimed principally at tobacco products.”

A Stash of Four Million Cuban Cigars

The domestic cigar manufacturers, and the politicians who represented them, celebrated the expansion of the embargo. The new restrictions proved far less popular, however, in countries such as Canada, Mexico and Spain because of its impact on local businesses that exported goods to the United States made of raw materials from Cuba. A number of the affected cigar companies were owned by Cuban businessmen who had fled their country after Fidel Castro expropriated the cigar industry in 1960. They had recently opened new manufacturing facilities in other countries, some of them using Cuban tobacco. Suddenly their cigars had become products non grata in the lucrative U.S. market.

One company, Menendez, Garcia y Cia., which made the renowned H. Upmann and Montecristo brands, was determined to continue its U.S. sales; it managed to take its case to the highest levels of the U.S. government—to President Kennedy himself. Co-managed by Alonso Menendez and José Manuel Garcia, Menendez, Garcia y Cia. had owned the H. Upmann factory in Havana. Menendez supervised the manufacturing of the cigars, while Garcia focused on sales. After its Cuban factory and brands were seized by Castro’s forces in 1960, leaving the owners without their business, the partners opened a new production facility in Spain’s Canary Islands.

Some of the cigars that they rolled in the Canary Islands were made from Cuban tobacco, according to government documents; indeed, prior to Kennedy’s decision to impose a full embargo on Cuban goods, the company had acquired enough Cuban tobacco to roll millions of cigars. “Prior to the date of the original Cuban embargo, the manufacturer, Mr. Garcia, acquired enough Cuban cigar filler tobacco from various countries, including the United States, and Cuban candela wrapper tobacco, from United States dealers, to manufacture approximately four million cigars in the Canary Islands,” wrote Secretary Dillon in a secret memo dated September 14, 1962. Tens of thousands of those cigars flowed into the U.S. in the weeks following February 7, 1962. With the March 23rd expansion of the embargo, however, those shipments were abruptly halted.

Ever the creative salesman, Garcia approached the Spanish government to intercede on behalf of the company. Spanish officials then requested a U.S. Treasury Department license for Menendez, Garcia y Cia. to continue to ship those four million cigars to the U.S. market at the rate of 200,000 a month over the next several years. Garcia presented a simple sales pitch: because the tobacco had been purchased before the embargo went into effect, blocking the import of these cigars would not advance the embargo’s objective—to deprive the Castro regime of foreign exchange.

But the Treasury Department still denied the import license. Garcia pushed, claiming that the cigars were not suitable for sale elsewhere, because they were green. Candela cigars, known then as American Market Selection, just weren’t in demand in Europe, Canada or elsewhere. “Candela-wrapped cigars are marketable,” argued Garcia, “only in the United States.”

Perhaps because of Kennedy’s well-known affection for the H. Upmann stogies, the Secretary of the Treasury felt compelled to brief the President, in minute detail, on the department’s “extensive inquiries” to verify “facts as to the sales of candela outside the United States.” Dillon’s memo provided a veritable tutorial to the White House on candelas and a window on the pricing of cigars at the beginning of the 1960s, true bargains when compared to today. “Garcia had contracted to sell his candelas to the United States at an average price of 27 cents,” read the memo, a premium over the 20-cent Cuban cigars sold to Canada around the same time. Garcia argued that Canadian duties on cigars were too high to allow them to be sold in the Great White North. Dillon ultimately concluded that Garcia could sell the cigars in non-U.S. markets, albeit at a lower profit margin. “Accordingly, we would propose to continue to deny Garcia’s license application, if you approve,” the Treasury Department memo concluded.

The President of the United States was now micromanaging the importation of cigars. “The President read the attached memorandum and told me to tell you that he approves of your proposal,” read a September 20, 1962, note from Kennedy’s personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, to Secretary Dillon. To fully close the tobacco loophole in the embargo, the President personally embargoed the last major shipments of Havana cigars destined for the U.S. market.

Sixty years later, those restrictions are still in place. They continue to block the importation of cigars rolled in Cuba into the United States, as well as cigars made anywhere else in the world with Cuban tobacco. Over the decades, the various U.S. trade sanctions against Cuba have been tightened and relaxed, depending on the politics of the day. But the total ban on Cuban tobacco remains in place—resulting, as Secretary of State Dean Rusk presciently predicted, “in considerable inconvenience to United States consumers.”