High Hopes For Jai Alai

The song is blaring, loudly, through the speakers at Miami’s Magic City Casino during an intermission between jai alai games on a Friday night. “Do you remember ... the 21st night of September? Love was changing the minds of pretenders ...” People sitting along the edge of the court, from teens to retirees, are singing along, some swaying in their chairs to the beat, listening to a tune that has been popular for nearly a half-century.

Thing is, this isn’t the version of “September” released in 1976.” The song that’s blaring is an update, the cover that Justin Timberlake and Anna Kendrick sung for the animated movie Trolls in 2016, weaving their style in with the original sound of the musicians who debuted it: Earth, Wind and Fire.

Fitting. A little of the old, a little bit of new. It worked for the song. Jai alai is trying the same ploy.

The sport was once such a big deal in Miami that it was included as part of the intro for episodes of “Miami Vice” and would routinely draw thousands of nattily attired people to gather, watch and bet. Now, it’s almost forgotten. The crowds are gone. Most frontons (the arenas where jai alai is played) are closed. Betting dollars go elsewhere.

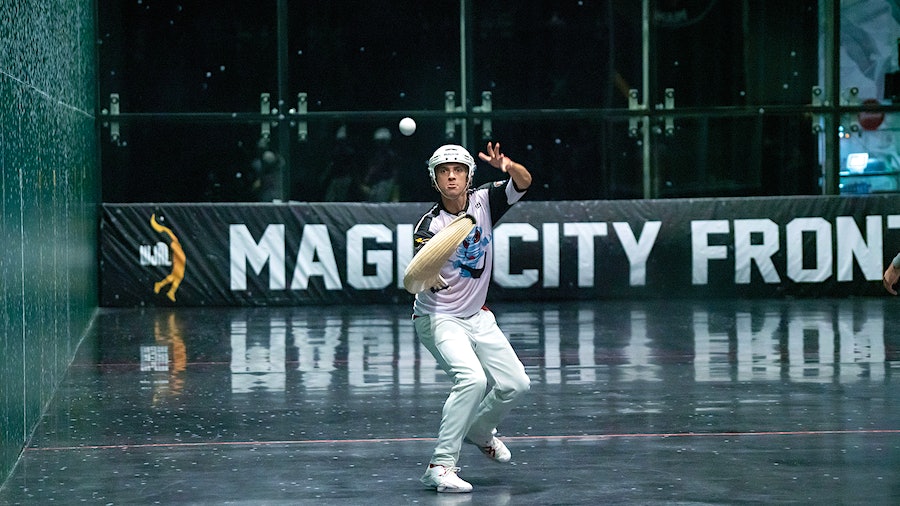

But hope has arrived in a new twist on the game. Called “Battle Court,” it has a team format with scoring reminiscent of tennis (first team to six points wins a set, first to win two sets wins a match. This is what the fans at Magic City are watching as waitresses in red dresses and black knee-high boots walk past with trays of drinks for those yelling “Vamos!” between points. One hundred, maybe 150 people, watch from the folding seats and a handful of circular black leather couches in a makeshift VIP area. It’s not like the old days. Yet.

“It’s like my dad always says,” says Chris Bueno, a second-generation player and part of the roster at Magic City. “Everybody loves jai alai. They just don’t know it yet.”

History says Bueno’s dad isn’t wrong.

Jai alai has worked in the U.S. before. Flourished, even. While the roots of the sport can be traced to the Basque region of 14th century Spain and France, it is believed that the first jai alai fronton in the U.S. was built for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. In Miami, awareness of the sport began at least in 1920, when The Miami Herald reported—in a story about the gambling options in Cuba—“after a careful inventory of the entire city, we are inclined to say that jai alai is the best thing that Havana has to show.”

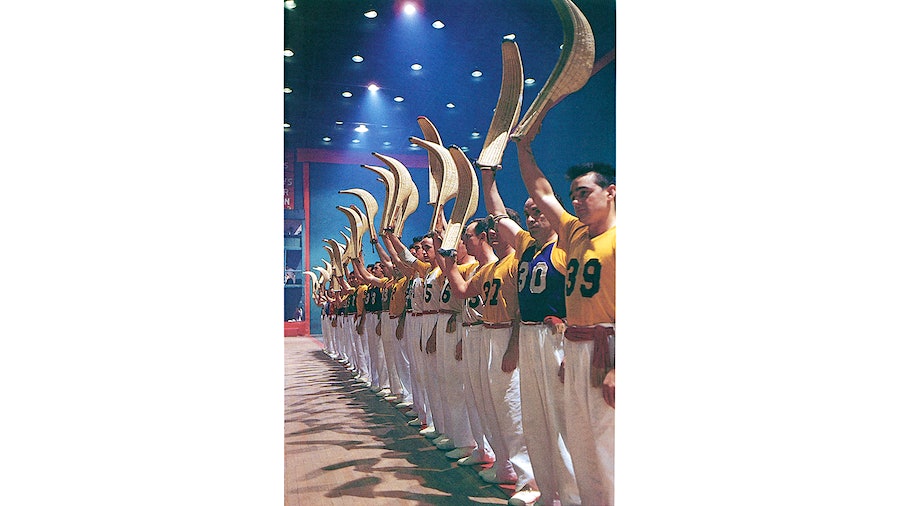

South Florida took notice. By November 1923, plans were in place to bring the game to Miami. In February 1924, it debuted, the players going by names like Epifanio, Legunda, Olaveaga and Azurmendi. Now, the names are Tennessee, Ikeda, Bueno, Jeden. Some are second- and third-generation players. Others are former University of Miami athletes who picked up the game a few years ago, recruited out of desperation as jai alai began its latest search for players who could keep the game alive.

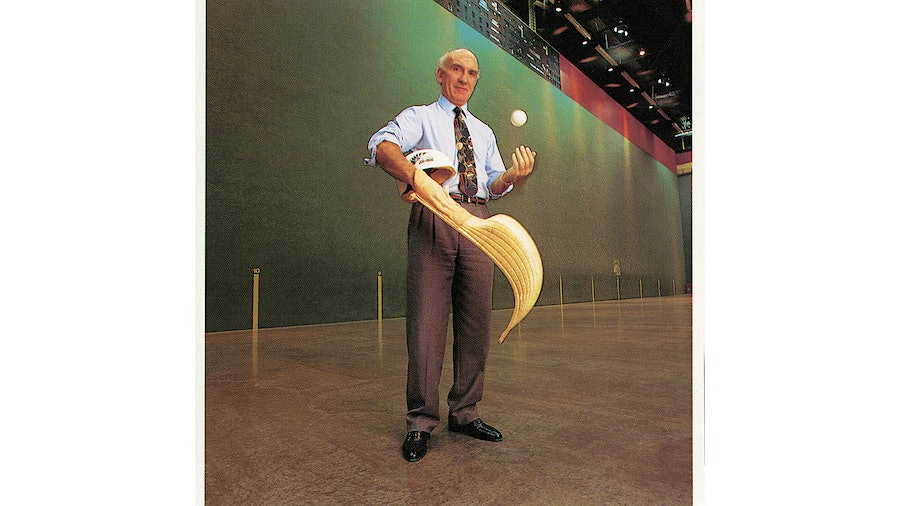

“The attraction was being told that, ‘You can’t revive it,’” says Scott Savin, the chief operating officer of Magic City Casino. “I don’t know if I knew anything more than anybody else knew. Everyone thinks we’re half crazy for doing this, or maybe I’m full crazy for doing this."

And somewhere along the way, that realization seemed to have become the selling point. The crazy, as Savin puts it, might be what makes jai alai attractive to a new audience.

In a time when surfing and skateboarding have been added to the Olympics, when sports like cornhole and axe throwing and even tag are drawing audiences on TV and in the streaming space, the hope is that jai alai can also carve out some viewership alongside football, basketball and baseball.

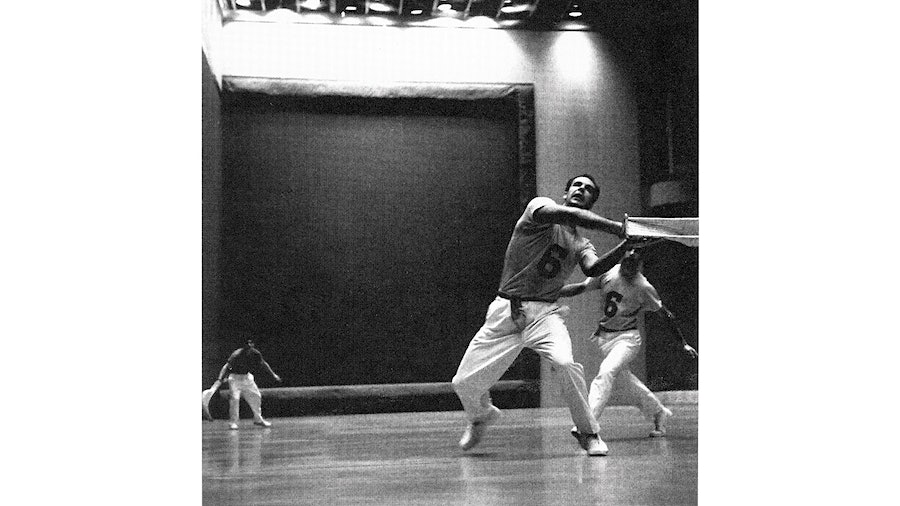

“The ball is going 125, 135, 140 miles per hour. These guys are making scoops and throws, and they’ve got this crazy thing on their arm. And all they wear is a helmet,” Savin says. “Football players have got all this padding on, hockey players have got all this stuff on. You want real athletes? You want the fastest ball sport in the world? Here it is. I mean, if we could somehow get the word out and make people sit up and take notice, I don’t know how they can’t like this game.”

Here are the basics: the ball (pelota) is hurled off a wall by a player using a wicker basket (cesta) wrapped to one of his arms. The ball must be caught and thrown in a smooth motion, ricocheting off the front wall of the three-walled court (the other walls are also in play), and must be played in the air or off no more than one bounce. Otherwise, the team or player tasked with catching the ball loses the point. Some games are one-on-one, others are two-on-two, a doubles format.

“If you can follow tennis,” Savin says, “you can follow jai alai.”

It used to be played—on some level, anyway—in many states; California, Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, Illinois, New York, and Connecticut among them. Parimutuel wagering kept it going in most of those places, but in time, with the advent of state lotteries and casinos, jai alai started losing the fight to grab its share of gamblers’ dollars. A game-fixing scandal in Connecticut didn’t help the sport’s popularity in the North.

Florida became the clear epicenter of jai alai in the U.S., but even in the Sunshine State the game was troubled for decades, and fronton owners blamed much of those issues on what they called stifling state taxes on the betting revenue. At one point, 78 percent of money wagered was going back to the bettors, with 22 percent going to the fronton. But it wasn’t quite that simple; out of that 22 percent, 32 percent was being paid right away in taxes. That left the frontons with about 14.9 percent of the betting revenue, from which expenses, salaries, benefits, and more taxes had to be paid.

Every few years, the question would be asked: Is this the end for jai alai?

A few times, the consensus has been “yes.” In recent years, bills passed by the Florida legislature regarding gambling have appeared to sound the death knell for the sport. (It now competes with casino gambling, although jai alai and horse racing remain the only legal forms of sports wagering in the Sunshine State.) Yet jai alai keeps going, reinventing itself a bit, marketing itself through TikTok and YouTube, and now it hopes to see benefits from a streaming deal with ESPN.

“It’s been very frustrating,” says 63-year-old Juan Ramon Arrasate—he’s just J.R. or Arra to most everyone at Magic City. He coaches the players at Magic City and has spent three-quarters of his life either playing or working within the sport. “But right now, we’re excited. We have to have some kind of base for it to work. We are getting there.”

Different ideas had to be brought to the table. A new wave of players—and a new wave of fans—had to be found. So, too, did new revenue sources. Savin came up with the idea to sell Battle Court franchises for $100,000 apiece, and it was about as honest a sales pitch as he could have managed: You’re not going to make money on this right now, he told potential investors. Somehow, they wrote checks anyway.

“The bottom line,” says Michael Blechman, who invested along with his wife Nina, “is that anyone who sees this loves it.”

He had lost touch with the game until a few years ago, when his son Andrew—a University of Miami graduate who had been part of the school’s television station and is a sports fanatic—called home with news of a lead on a job. The job: announcing jai alai.

Andrew Blechman sent his résumé with a note, describing himself as a “third-generation gambling degenerate” whose father had started taking him to jai alai when he was three years old. (Michael Blechman, who made his money in the specialty printing business, doesn’t hide the fact that he bets on the occasional horse or two.)

Magic City was intrigued, though still skeptical.

“They contacted him back and they said to him, ‘What do you know about jai alai? You’re 21 years old. No 21-year-old knows anything about jai alai,’” Michael Blechman recalls. Turned out, the kid aced their test on the rules of the game. He got hired for $500 a week at first, then saw the position evolve into more responsibility.

And just like that, Michael and Nina Blechman—Illinois residents who often fly to South Florida to watch in person and never miss a game that is streamed online—were back into jai alai.

“I’m 67 years old,” Michael Blechman says. “Back in the day, when you made your reservations to go to Florida, you got an airline ticket, you got a hotel reservation, and then you got your jai alai tickets ... because it was fantastic.”

Jean Gregory Melendo Ikeda—he goes just by Ikeda on the court—wants to experience those days for himself.

His grandfather played the game. So have an uncle, some cousins, his father and more. His grandmother, who lives just over the Mexican border south of San Diego, watches every time he plays. Every time. She takes copious notes and texts them to Ikeda after every game. When he wins, the notes are good. When he loses, he dreads seeing the text.

Ikeda was a lab technician before his jai alai opportunity came.

“It’s in my heart,” he says. “It’s not just for money, probably it’s more the pride. It’s more that you want to prove that today is my day. Maybe tomorrow is your day, but I’m going to prove that today, I’m going to be the best. It’s unexplainable. It’s super exciting. It’s more than just a game. It’s my family. It’s my family.”

Players can make somewhere between $45,000 and $100,000 a year based largely on performance, with some benefits, Savin says. Many have side jobs. Some drive for ride-share companies, some coach baseball, one is a financial advisor and Bueno and his wife are in the mortgage and real-estate business.

The Magic City court is considerably smaller than the traditional fronton; about 60 feet shorter, which makes the needed reaction times faster. Bueno’s father played on the bigger court at Miami Jai Alai, and just thinking of those days makes Chris Bueno nostalgic. “I love watching the big court, man. I just love it,” Bueno says. “To me it has a sentimental value, but playing here also, it’s the same sport with a couple different features. It’s not a completely different game.”

Well, it can seem that way at first.

Tanard Davis—he goes by Jeden in jai alai—played football for the Miami Hurricanes and has a Super Bowl ring from his time as a practice-squad member with the Indianapolis Colts. He was one of the Miami athletes who got an email from his alma mater saying a playing opportunity was available. Problem was, most of those athletes had no idea what a cesta, pelota or fronton even was.

Now, they’re experts. And ambassadors. And the sport’s hope. “We’re doing something that’s never been done in jai alai,” Davis says.

They got there by taking a leap of faith. Darryl Roque—he goes by Tennessee, a nod to his home state—ignored the first call from the Hurricanes for help. The second one got him thinking that maybe his days of being a pro athlete weren’t over after all.

“I got the email back in 2017,” Roque says. “The first email, I did not respond to because I thought it was something fake. And then I saw a second email and I followed up with it, because I actually paid attention to see who it was from. It was from the alumni department at University of Miami, the athletic department.”

That phone call led to an invitation: Go to the fronton in Dania Beach, Florida, and try out. He was handed a cesta. He had no idea what to do with one. Someone showed him how to tie it onto his wrist, and he stepped onto the court. Roque—who had played baseball in the Montreal Expos and Baltimore Orioles organizations—was a full-time teacher at that point. It didn’t take long before jai alai became the priority.

“It’s my competitive nature. I just always strive to be the best,” says Roque, now 45. “I first got drafted by the White Sox. I said, ‘I want to win a national championship in college.’ My first year at University of Miami, we did not end up winning. My second year, I came back. I didn’t care about getting drafted. I wanted to win a national championship. We ended up winning the national championship my senior year. And then I ended up playing professional baseball. I’m hardheaded. So, if somebody tells me that I cannot do something, all right, you dared me. I’m going to go do it.”

Roque wasn’t just along for the ride. He went 5-1 in that senior season, pitching the Hurricanes past Alabama in the game that clinched a berth in the College World Series title.

Now, six points, not runs, is the target score Roque seeks. First player or first team to six points wins the set at Magic City. The players are going head-to-head on the court, and they know they’re all in it together off the court—some have even introduced the game to elementary-school-aged kids, with smaller cestas and plastic pelotas. Maybe, just maybe, they hope, those kids could be the future of a sport that desperately needs one.

They’re trying. The helmets remain on, the pelotas still fly, and there’s a belief that the game can grow again.

“Everybody’s written the obituaries for jai alai time and time and time again,” Blechman says. “Look, it’s not my initial jai alai. That’s never coming back. This format is more understandable. So, yes, this is not your father’s jai alai, my father’s jai alai. It’s not. This is better.”